The idea that we need to “think outside of the box” to solve problems is frustratingly vague. Fortunately, there are several mental strategies that can promote creativity, including thinking nonlinearly and counterfactually. But one of the most underutilized processes is asymmetrical thinking, which involves flipping around and reshuffling ideas to unearth hidden imbalances.

This mindset is useful across disciplines, including physics, economics, biology, business, and investing. Its origins, however, are from geometry.

The dance of symmetry and asymmetry

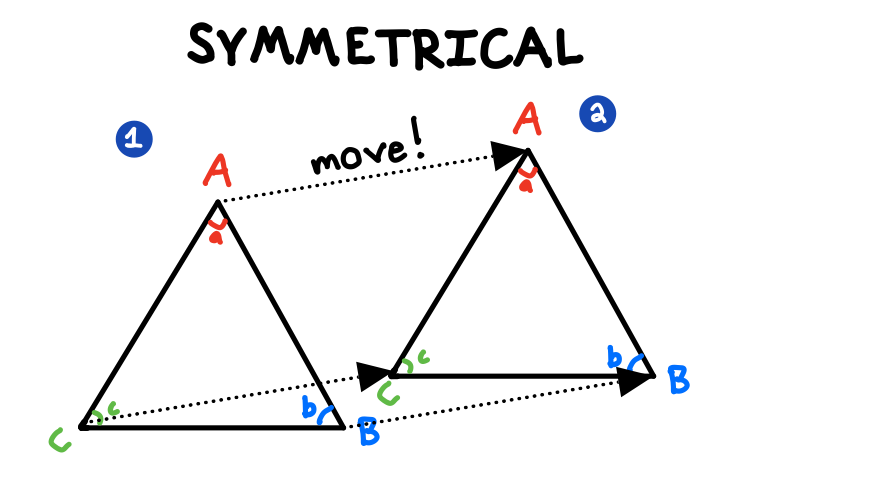

The basis of geometry is symmetry, which describes the property of an object being unaffected by undergoing some transformation. Consider an equilateral triangle. If we move the whole shape an inch to the right, the angles and dimensions of the triangle are unchanged; that is, they are symmetrical with regards to this simple translation.

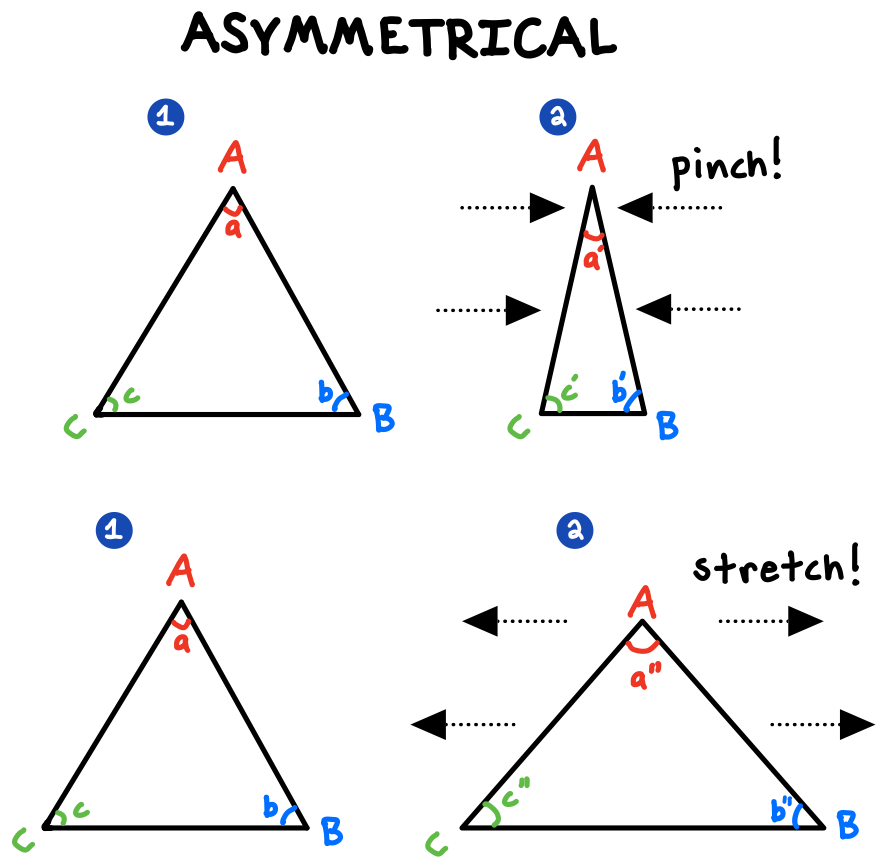

On the flip side, asymmetry is simply the absence of symmetry, indicating that an object is affected by undergoing some transformation. If we take our original triangle and pinch or stretch it, the lengths and angles of the triangle will change—they are asymmetrical with regards to pinching or stretching.

Ancient scholars, particularly Euclid, harnessed the concepts of symmetry and asymmetry in shapes to discover revolutionary geometrical and mathematical principles, setting the foundation for modern physics, engineering, and more.1

Outside of geometry, asymmetry offers an invaluable mental model: it can be extremely insightful to flip things—whether shapes, ideas, relationships, or strategies—backwards and forwards and see whether what is true in one direction is also true in the opposite direction—in other words, whether there is symmetry. In our lives, finding asymmetries presents opportunities for unearthing unique insights, stimulating creative ideas, and creating leverage to drive outsized impact.

Asymmetries all over

Physics

In physics, practically all laws of nature originate in symmetries and asymmetries. Emmy Noether’s groundbreaking 1915 theorem connected symmetries in nature with the universal laws of conservation. Her work showed that whenever we see some sort of symmetry in nature, there must also exist a corresponding “conserved” element which preserves the symmetry.2

For example, it’s well-established that the laws of physics are uniform throughout the universe. Regardless of where we are, the laws of nature remain unchanged (symmetrical), just as the angles of our triangle did not change when we moved it. This symmetry gives birth to principles such as the the “law of conservation of momentum,” which holds that unless an outside force (such as friction or air resistance) intervenes, the momentum of a system will remain unchanged.3

Biology

Nature abundantly showcases symmetry.

Most vertebrates, from humans to elephants, have two “halves” that are roughly equal. This property, called “bilateral symmetry,” is believed to be advantageous for efficient movement and centralized control of sensory organs in the “head” of the organism. Greater symmetry also correlates with higher rates of reproduction, since many organisms with greater symmetry tend to be preferred as mates (example: facial symmetry in humans).4

However, it’s important to note that asymmetry is also an important and widespread trait, even in humans. Consider the phenomenon of “handedness,” the left lung being smaller than the right, or the left and right brain controlling different cognitive functions.

Statistics

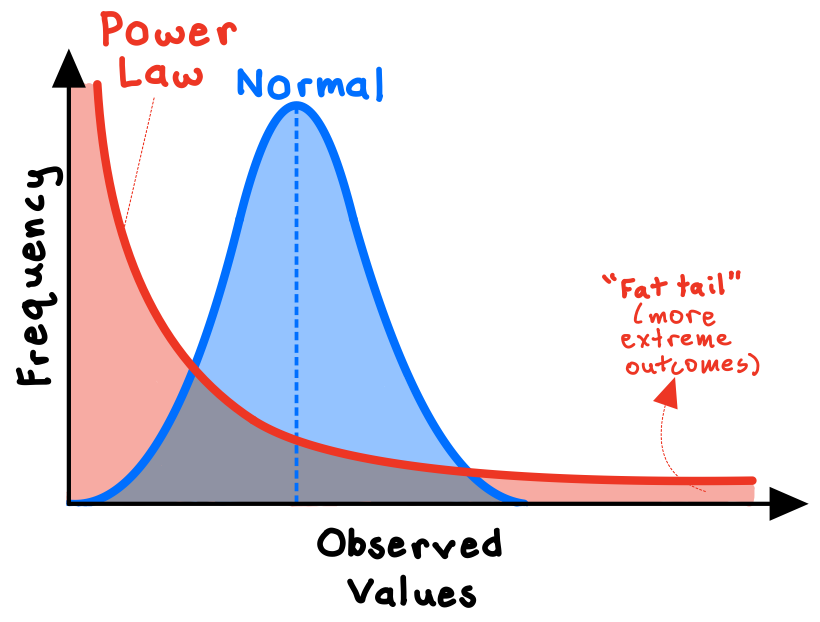

Picture the symmetrical “bell curve” of the normal distribution. For any given random observation, there’s an equal probability that it will fall above or below the central average of the data—such as with human height and weight.

However, many real-world events generate results that are in fact asymmetrical (or “skewed”) rather than normal. Some produce “power-law” distributions in which a few extreme values dominate over the modest majority, such as with the frequency of words in most languages, the magnitude of earthquakes, and city populations.

Business and Investing

In the world of venture capital (“VC”), investors bet on risky, early-stage ventures, which carry both high potential growth and high risk of failure.

Unsurprisingly, the financial returns of early-stage startups are power-law distributed. Most investments generate low or negative returns, but a few bets generate enormous returns. VCs are essentially in pursuit of asymmetrical returns, aiming to own a piece of occasional breakout successes such as Google or OpenAI.

They gladly accept that many (even most) of their investments will generate little or no return, as long as one or two investments become wildly successful. The most they can lose is 1x their money, but the extreme winners could generate 10x, 100x, or more.

Using asymmetry as a strategy

In the competitive realm, one indirect strategy involves using your relative advantage to impose asymmetric costs on the opposition. In military conflicts, for example, weaker insurgent factions may compensate by using asymmetric warfare tactics, such as by attacking the opponent’s electrical grids, roads, or water supply.

In business, the basic concept of competitive advantage is rooted in differences—in the asymmetries among competitors. The task falls to the leaders to identify the asymmetries that can be turned into advantage and exploited, such as a valuable patent, strong network effects, or significant economies of scale.5

A great example is Netflix’s critical insight around 2011 to commit substantial resources towards producing original content. Historically, Netflix and its competitors licensed a portfolio of content produced by other companies. This meant that every new subscriber increased content costs. With Netflix’s landmark pivot to producing its own original content—particularly early shows such as Lilyhammer and House of Cards—Netflix turned content into a fixed cost.6 With original content, more subscribers don’t directly increase content costs.

This strategy created a cost asymmetry between Netflix and its competitors: Netflix’s content costs would become cheaper over time on a per-subscriber basis, as it spread its fixed costs over a larger number of subscribers! Netflix would lead a global revolution in the production of original streaming content.

***

Asymmetry is much more than an academic concept—it offers a powerful new lens through which we can view the world. By identifying and leveraging the hidden asymmetries in our lives, we can open the door to inventive solutions and strategies. As we navigate challenges in our own lives and careers, we should consider how asymmetrical thinking might offer unexpected answers.

Notes

- Ellenberg, J. (2021). Shape. Penguin Press. 52-58.

- Angier, N. (2012, March 26). The Mighty Mathematician You’ve Never Heard Of. The New York Times.

- Feynman, R., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (2010). The Feynman Lectures on Physics (3rd ed., Vol. I). Basic Books. 10-2.

- Toxvaerd, S. (2021). The Emergence of the Bilateral Symmetry in Animals. Symmetry, 13(2), 261.

- Rumelt, R. (2011). Good Strategy/Bad Strategy. Crown Business. 160-164.

- Helmer, H. (2016). 7 Powers. Deep Strategy LLC. 20-22.