“Complex systems—the term of art for many interacting agents, whether buyers and sellers in markets, employees and managers in companies, or the atoms and molecules of a turbulent river—have earned that term for a reason. Their most interesting questions rarely have simple answers.”

Safi Bahcall, Loonshots (2019, pg. 227)

Complex systems are collections of simpler components that are interconnected in such a way that they “feed back” onto themselves to create their own complex (or “emergent”) patterns of behavior—collective behaviors which cannot be defined or explained by studying the individual elements.

Complex systems are everywhere. Examples include humans, animals, plants, insect colonies, brains, organizations, industries, economies, ecosystems, galaxies, and the Internet. Their basic operating units are feedback loops—causal connections between the stock levels of the system and the rules or actions which control the inflows and outflows.

Complex systems are inarguably one of the most valuable mental models to understand, because most of what we do takes place in complex systems. Yet we routinely ignore and underestimate their dynamics! Adopting “systems thinking” can help us enact positive change and make drastically better decisions.

Producing complex behavior

Consider the population of a country. Let’s define the flows that control a nation’s population as the birth rate and death rate (assuming, for simplicity, that there is no migration). If the birth rate exceeds the death rate, the population will grow—a reinforcing (positive) feedback loop. But it cannot grow forever.

Eventually, the system will produce its own balancing (negative) feedback loops to attempt to constrain future population growth. For instance, excessive population levels will eventually strain the country’s resources, potentially leading to increased deaths due to lower living standards, food shortages, or degraded health care. Sensing these problems, people may choose to have fewer children in the future (or the government may mandate it). Savvy innovators may create new technologies to mitigate society’s challenges. The cumulative effect of all this negative feedback is likely to be a moderation of population growth.

This example illustrates how a the relationships between a system’s stocks and flows can produce unique, higher-order patterns of behavior. Amidst constant change, the system attempts to “self-regulate” into a long-term equilibrium.

Why we get systems so wrong

Systems are incredible: they can adapt, respond, pursue goals, repair themselves, and preserve their own survival with lifelike behavior even though they may contain non-living things. Human society itself is a remarkable example, with networks of individuals, organizations, and governments acting individually and collectively to create the conditions for human thriving.

However, systems are also frustrating: the goals and behaviors of their subunits (individual countries, organizations, groups, leaders, citizens, etc.) may create system-level outcomes that no one wants, such as hunger, poverty, environmental degradation, economic instability, unemployment, chronic disease, drug addiction, and war.1

It is easy to fall into traps of overconfidence and illusions of control when dealing with complex systems. We prefer a world that we can explain with simple, coherent narratives and familiar patterns to one riddled with randomness and uncertainty.

The uncomfortable truth is that accurately predicting and influencing the behavior of complex systems is extremely difficult. When multiple feedback loops are jostling for dominance, small changes in the environment can produce large, nonlinear changes in the system. Consider the impossibility of perfectly forecasting stock market crashes, terrorist attacks, or even the weather.

The environment changes over time and as we and others interact with it, and as behavior by one element reverberates into subsequent behaviors in other elements, or even in other systems. Consequently, our knowledge of complex systems must necessarily be piecemeal and imperfect.2

We cannot control complex systems, but we can seek to understand them in a general way and prepare to adapt when they inevitably surprise us.

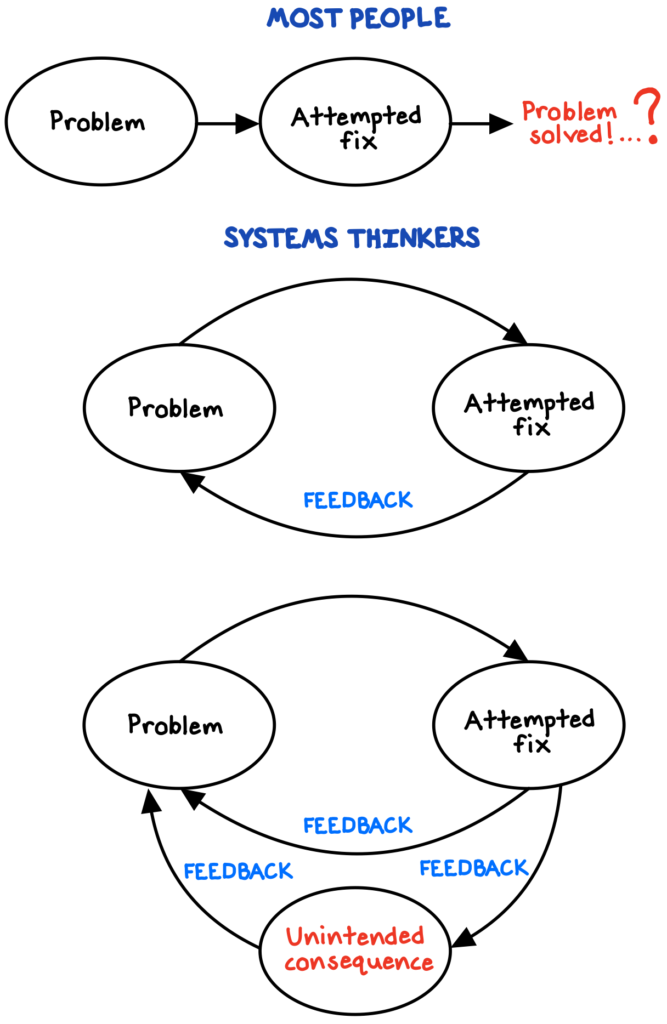

The consequences of non-system solutions to system problems

We should be extremely cautious about pursuing rigid, short-term solutions to issues that are fundamentally systems problems, because we cannot be certain that such actions won’t cause more unintended harm than good.

Many well-intended policies seeking to address such problems may “sound” good but have only short-term benefits, or fail to achieve their goal altogether. Worse, they could exacerbate the problem or even create entirely new problems.

There are no “easy” solutions to problems such as public health, economic growth, homelessness, public education, or terrorism.

Consider the following examples of non-systems solutions gone wrong:

- The U.S. experiment with the prohibition of alcohol in 1920 led to a violent spike in crime, and alcohol consumption actually increased.3

- In the 1930s, Australia introduced the cane toad species to control the cane beetle, which was a major pest for sugar cane. With few natural predators, the cane toad itself became invasive. It not only failed to control the cane beetles, but also devastated other species with its toxic skin and created entirely new ecological problems.4

- Several Asian governments exerted extreme state control over their economies in the late 20th century, including Korea (1960s), China (1979), and Vietnam (1990s). These policies were very effective at keeping inequality down, but at an enormous cost in terms of growth—reducing living standards for everyone!5

- China’s decades-long “One Child” policy indoctrinated many Chinese parents to believe that their resources are best devoted to one child, permanently changing the country’s population dynamics. A cultural preference for boys encouraged sex-selective abortions and contributed to a lopsided gender ratio. And brutal enforcement tactics included illegal forced abortions and sterilizations.6

A better approach to solving complex problems

“If you wish to influence or control the behavior of a system, you must act on the system as a whole. Tweaking it in one place in the hope that nothing will happen in another is doomed to failure.”

Dennis Sherwood, Seeing the Forest for the Trees (2002, pg. 3)

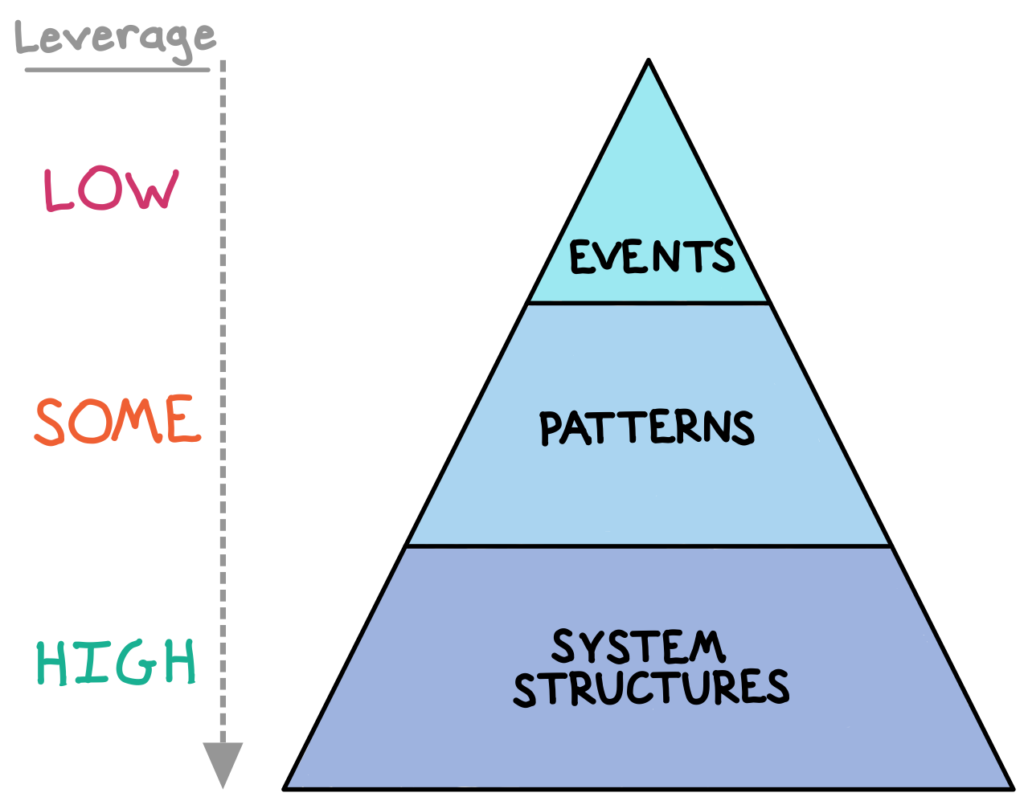

Before we attempt to nudge a complex system safely towards change, we must look beyond the “event” level (today’s happening) in order to understand the system’s patterns of behavior over time (its dynamics). This requires substantial observation and study. With this knowledge, we can begin to unearth and act on the systems structures that give rise to those behaviors.7

It is here, at the system level, where we are most likely to unearth high-leverage places for intervention and anticipate unintended consequences. We call this problem-solving approach “systems thinking”—one of the most valuable mental frameworks available to us.

For example, let’s contrast China’s blunt “One Child” policy, which aimed to curb population growth, with Sweden’s population policies during the 1930s, when Sweden’s government became concerned after a substantial decline in birth rate. Sweden could have adopted, say, a simple “Three Child” policy to force parents to accelerate population growth. Instead, the Swedish government recognized that there would never be agreement about the appropriate size of the family. But there was agreement about the quality of child care: they determined that every child should be wanted and nurtured.

Under this principle, they adopted policies that provided widespread sex education, free contraceptives and abortion, free obstetrical care, simpler divorce laws, support for struggling families, and substantial investments in education and health care. Since then, Sweden’s birth rate has fluctuated up and down, but there is no crisis, because people are focused on a much more important goal than the number of humans in Sweden: the quality of life of Swedish families.8

***

The fact that we live in a world of unpredictable and interconnected complex systems should be humbling and encourage us all to embrace lifelong learning. We should experiment incrementally, monitor vigilantly, and be willing to adapt based on what we learn. Be skeptical of seemingly straightforward solutions to complex problems. Consider what second- and third-order side effects there could be, and have the courage to question popular convention.

Notes

- Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing. 1-7.

- Kay, J. (2010). Obliquity. The Penguin Press. 12-14.

- Blocker Jr., J. (2006). Did Prohibition Really Work? Alcohol Prohibition as a Public Health Innovation. American Journal of Public Health, 96(2), 233-243.

- Australia Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. (2010). The cane toad (Bufo marinus) – fact sheet. DCCEEW.

- Banerjee, A., & Duflo, E. (2019). Good Economics for Hard Times. PublicAffairs. 57-61.

- China rapidly shifts from a two-child to a three-child policy. (2021, June 3). The Economist.

- Kim, D. (1999). Introduction to Systems Thinking. Pegasus Communications. 17-18.

- Meadows, D. (2008). 115-116.