“Spend each day trying to be a little wiser than you were when you woke up. Discharge your duties faithfully and well. Step by step you get ahead, but not necessarily in fast spurts… Slug it out one inch at a time, day by day. At the end of the day—if you live long enough—most people get what they deserve.”

Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie’s Almanack (2005, pg. 138)

There is perhaps no more fundamental idea that reminds us of the value of the twin virtues of patience and discipline than the phenomenon of compound interest.

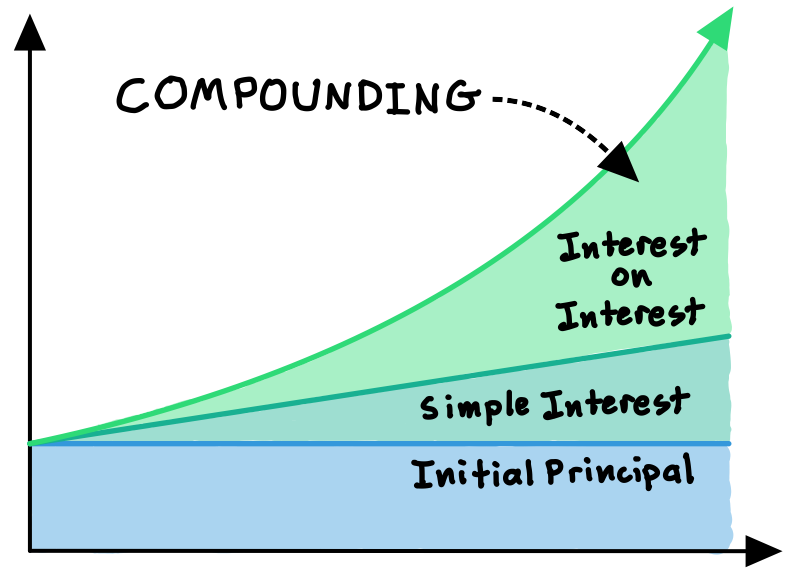

Compounding describes the process by which a fixed quantity (such as a savings account) grows by accruing “interest” at a certain rate, then earning interest on the original quantity plus interest on the newly added interest, and so on.

Not so simple

Compounding is a powerful example of a reinforcing (positive) feedback loop, which produces an exponential growth effect in which the absolute growth in the quantity increases over time. In contrast, “simple interest” produces linear growth in which the balance increases by a constant absolute amount each period.

For example, a savings account with an initial balance of $10,000 that earns 5% simple interest will grow by exactly $500 each year (see simplified chart below). If that same $10,000 were to instead earn 5% compound interest, the balance would grow by $500 in Year 1, $525 in Year 2, $551 in Year 3, and (skipping ahead) $776 in Year 10, etc.—generating a nonlinear increase in value over time.

The mathematical phenomenon of compounding is one of the most powerful concepts to understand, with applications for our personal financial management, our habits and productivity, and indeed our pursuit of wisdom generally.

The best for last

Compounding teaches us to be patient, because most of the benefits of compounding come at the end! Whether we’re starting to build up our retirement savings, creating new relationships, or establishing better habits, we may not see huge benefits up front. But if we combine the discipline and patience to keep making incremental improvements, over time we can generate enormous results.

“Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. They don’t seem like much on any given day, but over the months and years their effects can accumulate to an incredible degree.”

James Clear (2018, on Twitter), author of “Atomic Habits”

In financial decisions, it is critical to value cash flows not based on their absolute value today, but on their opportunity cost—the potential value of that cash flow if we had instead invested it and allowed it to compound over time. Any use of money must justify the opportunity cost of foregone compound interest on those funds—and that amount could be huge.

Disciplined investors are “cursed” with viewing investments and expenses through this lens. Warren Buffett famously quipped that his worst investment ever was actually his purchase of Berkshire Hathaway. He estimated that if he had simply taken the amount he paid in 1962 and invested it at the rate of return he would go on to earn over his career, he would have accrued $200bn more wealth.1

Stop trading so much

If I could summarize the one lesson about money that I’ve learned in my own career in finance and strategy, it would be that people (especially men) generally overestimate their own financial acumen.

Overconfidence in finance leads us to transact much more often than we should—and transactions are costly, because they counteract the power of compounding.2 Every time we sell a stock or asset, we pay some transaction fees, and we owe taxes on any gains we accrue. As compounding teaches us, the value of these costs rises exponentially over time, since we could have simply let those funds compound freely.

“Beware of little expenses: a small leak will sink a great ship.”

Benjamin Franklin

The more actively that individual investors trade, the more money they typically lose. A fascinating study observed that if we break out the returns of individual investors into tiers based on how frequently they trade, the net returns of every group except for the least frequent traders are lower than the net return from simply investing in an S&P 500 index fund. And the group with the heaviest traders generated the lowest returns, by far.3

My advice: unless we are market geniuses (most of us aren’t), we probably shouldn’t be trading frequently. Most likely, we would be better off in the long-term by investing the majority of our portfolios in low-cost, passive “index funds” (which simply mirror the returns of a market index)—only infrequently checking our balance or executing transactions.

Learning begets learning

Perhaps the most powerful case of compounding is knowledge growth itself.

Wisdom is not a matter of collecting facts and clever examples. Being a polymath is the “simple interest” version of learning. Rather, the way we compound our knowledge is by incrementally building up a self-supporting, interconnected foundation of ideas and explanatory frameworks—a “latticework,” to borrow Charlie Munger’s terminology.

The human brain learns by association, the cognitive processes in which we attempt to draw meaningful connections between a new piece of information and our prior knowledge. We compare, combine, and create variations between different ideas.

Developing a strong foundation of models and ideas in our heads enables a positive feedback loop: more information supplies more possible connections, which helps us improve our knowledge, which makes it easier to add more information and make even more meaningful connections, and so on.4 In other words, learning compounds to facilitate more learning.

This happens through independent reading, research, and elaboration—by following our curiosity and thinking critically about different (often incompatible) ideas and how we might combine them with other knowledge. The more diverse these ideas are across disciplines (physics, systems, economics, etc.), the stronger the foundation will be.

By committing to a lifelong process of learning in this associative, multidisciplinary way, our knowledge can truly compound to empower us to solve an incredible range of problems.

***

The key lesson? Diligently pursue incremental improvements, then simply be patient. Let compounding work its magic! With time, the odds tip heavily in your favor.

Notes

- Crippen, A. (2010, October 18). Warren Buffett: Buying Berkshire Hathaway Was $200 Billion Blunder. CNBC.

- Daniel, K., & Hirshleifer, D. (Fall 2015). Overconfident Investors, Predictable Returns, and Excessive Trading. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(4), 61-88.

- Barber, B., & Odean, T. (April 2000). Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors. The Journal of Finance, LV(2), 773-806.

- Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes (2nd ed.). Independently published. 49-54, 130-133.