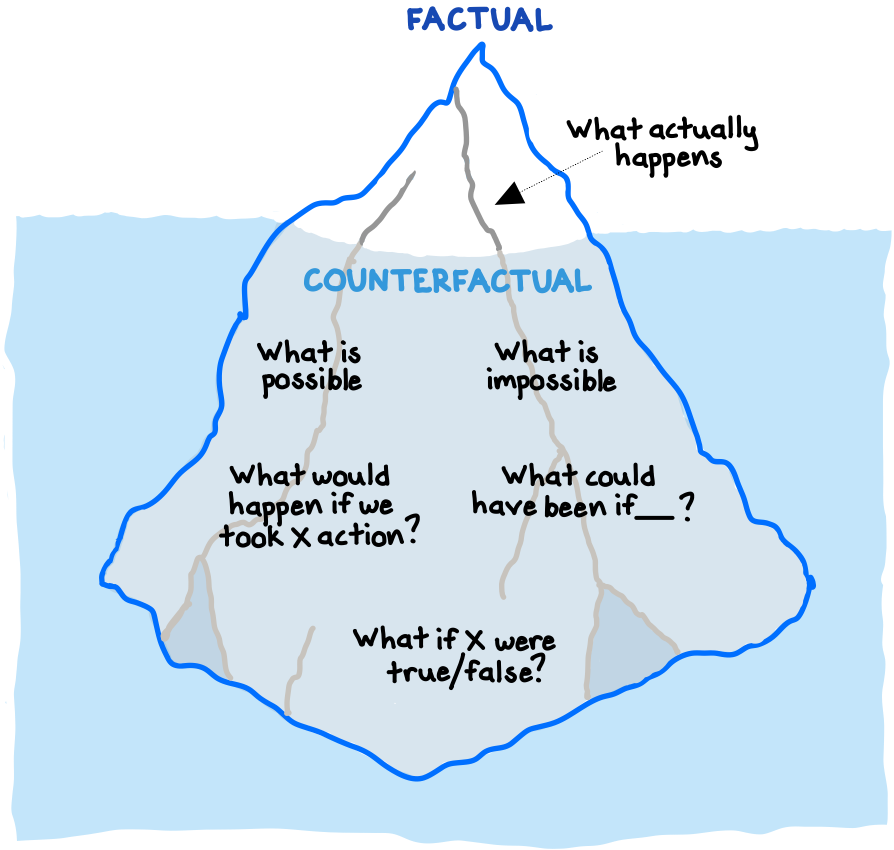

A counterfactual is a “what-if” scenario in which we consider what could have been or what could happen, rather than just what actually happens. What if I had never met my partner? What if the US had never invaded Iraq? How might our customers react to a price increase?

Thinking in counterfactuals is a quintessential exercise in human creativity. By imagining what is possible or what could have been under different circumstances, we can unlock new solutions, better evaluate past decisions, and uncover deeper explanations of the world than we could by analyzing only what happens.

No, AI isn’t about to take over the world

To appreciate the power of counterfactual thinking, consider the capabilities and limitations of artificial intelligence (“AI”) technologies, specifically generative chatbots such as ChatGPT.

These chatbots leverage intricate machine learning (“ML”) networks to simulate human conversation. For instance, if we feed a chatbot millions of lines of dialogue from the Internet—including questions, answers, jokes, and articles—it can then generate new conversations based on patterns it has learned and convincingly mimic human interactions, using mindless and mechanical statistical analysis.

However, despite exponential improvements, AI chatbots struggle mightily with genuine counterfactual thinking. Unlike humans, their ability to explain the world or dream up entirely new scenarios is constrained by their explicit programming.1 They cannot disobey, or ask themselves a different question, or decide they would rather play chess. Instead, they assemble convincing responses to prompts by reassembling their training data. Until we can fully explain how human creativity works—a milestone we are currently far from reaching—we won’t be able to program it, and AI will remain a remarkable but incomplete imitation of human-level creative thought.2

“Becoming better at pretending to think is not the same as coming closer to being able to think. … The path to [general] AI cannot be through ever better tricks for making chatbots more convincing.”

David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity (2011, pgs. 157-158)

Contrary to the popular AI “doomsday” paranoia, this idea paints a hopeful picture. While digital systems continue to automate routine tasks3—such as bookkeeping, analytics, manufacturing, or proofreading—our counterfactual abilities enable us to push the boundaries of innovation and creativity, with AI as our aid, not our replacement.

We should, therefore, dedicate ourselves to solving problems that require our unique creative and imaginative powers—to design solutions that even the most powerful AI cannot. We did not invent the airplane, nuclear bomb, or iPhone by regurgitating historical data. We imagined good explanations for how they might work, then we created them!

Error-correcting with counterfactuals

Over countless generations of genetic evolution, our brains have developed remarkable methods of learning. The first, more “direct” method of learning is through rote trial-and-error, which can help monkeys to figure out how to crack nuts or chess players to devise winning strategies.

The second, which is a human specialty, is through simulation—using hypothetical scenarios to evaluate potential solutions in our minds. Because blind trial-and-error can sometimes lead to tragedy, an effective simulation is often preferable, and sometimes necessary.4 This strategy is evident in flight training, surgical practice, war games, nuclear reactions, and natural disasters.

In fact, counterfactuals are crucial to the knowledge creation process. It always starts with creative guesswork (counterfactuals) to imagine tentative solutions to a problem, followed by criticism of those hypotheses to correct or eliminate bad ones. We evaluate a candidate theory by assuming that it is true (a counterfactual), then following it through to its logical conclusions. If those conclusions conflict with reality, then we can refute the theory. If we fail to refute it, we tentatively preserve it as our best theory, for now.

Let’s try it out with a problem of causality. We’ve all heard that “correlation does not imply causation,” but our instinct to quickly explain things in terms of linear cause-effect narratives still misleads us. To truly establish causality, we must turn to counterfactual reasoning. In general, we should conclude that an event A causes event B if, in the absence of A, B would tend to occur less often.5

Consider the claim that vaccinations cause autism in children, a tempting headline for the conspiracy-minded. Following our counterfactual logic above: if this theory were true, we should expect autism to be more common among vaccinated children. However, the evidence suggests that rates of autism are essentially equivalent between vaccinated and unvaccinated children.6 In reality, vaccination administration and the onset of autism simply happen (coincidentally) around the same age.

“The science of can and can’t”

A thrilling application of counterfactuals comes from physics, where theoretical physicists David Deutsch and Chiara Marletto are pioneering “constructor theory,” a radical new paradigm that aims to rewrite the laws of physics in terms of counterfactuals, statements about what is possible and what is impossible.

Traditional physical theories, such as Einstein’s general relativity and Newton’s laws, have focused on describing how observable objects behave over time, given a particular starting point. Consider a game of billiards. Newton’s laws of motion can predict the paths of the balls after a cue strike, based on initial positions and velocities. However, it remains silent on why a ball can’t spontaneously jump off the table or turn into a butterfly mid-motion.

Constructor theory goes a level deeper. Instead of merely predicting the balls’ trajectories, it might explain why certain trajectories (such as flying off as a butterfly) are impossible given the laws of physics. By focusing on the boundaries of what is possible, counterfactuals enable physicists to paint a much more complete picture of reality.

Using counterfactuals, constructor theory has offered re-formulated versions of the laws of thermodynamics, information theory, quantum theory, and more.7

***

In summary, we should embrace our beautifully human capacity to imagine worlds and scenarios that do not exist. Counterfactual thinking can spark creativity and innovation, help us reflect on the past, enable better critical evaluations, and even reimagine the laws of physics. Plus, it is the best defense we have against automating ourselves away!

What world will you dream up next?

Notes

- Pearl, J. (2019). The Limitations of Opaque Learning Machines. In J. Brockman (Ed.), Possible Minds. Penguin Press. 15-19.

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The Beginning of Infinity. Penguin Books. 154-158.

- Autor, D. H., & Dorn, D. (2013). The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the US Labor Market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1553-1561.

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. 73-77.

- Spiegelhalter, D. (2021). The Art of Statistics. Basic Books. 96-99.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Autism and Vaccines. CDC.

- Marletto, C. (2021). The Science of Can and Can’t. Viking. xvi-xix.