“I may be wrong and you may be right, and by an effort, we may get nearer to the truth.”

Karl Popper, The Myth of the Framework (1994, pg. xii)

Scientific theories are explanations—statements about what is there, what it does, and how and why. The distinctive creativity of human beings manifests in our capacity to create new explanations, to create knowledge.

But how do we create knowledge? In short, it consists of guessing, then learning from our mistakes—a form of trial-and-error. Unfortunately, two common misconceptions in particular plague our understanding of this process, leading us to embrace bad ideas.

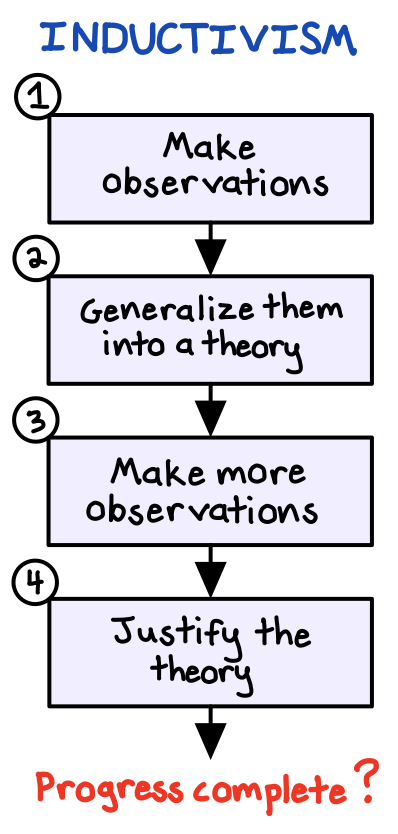

The induction misconception

One of the classic fallacies about knowledge creation is that of “inductivism”—the belief that we “obtain” scientific theories by generalizing or extrapolating repeated experiences, and that every time a theory makes accurate predictions it becomes more likely to be true. But this whole process is non-existent.

First of all, the aim of science is not to simply make predictions about experiences; it is about explaining reality. Completely invalid theories might make accurate predictions.

Consider Bertrand Russell’s famous story of the chicken. A chicken observed that the farmer stopped by every day to feed her, “extrapolating” from this observation that the farmer would continue to do so. Every day that the farmer came to feed the chicken, the chicken became more confident in her “benevolent farmer” theory. Then, one day, the farmer came and wrung the chicken’s neck. Unfortunately, the extrapolating chicken had the wrong explanation for the farmer’s behavior. We cannot assume that the future will mimic the past without a valid explanation for why the past behaved as it did, and why we should expect that behavior to continue.1

Second, we are capable of creating explanations for phenomena that we never experience directly (such as stars, black holes, or dinosaurs), and for phenomena that are radically different from what has been experienced in the past. What is needed is an act of creativity. We did not “derive” atomic bombs or airplanes from past experience; we discovered good explanations about them, then we created them.2

So much for inductivism.

The justification misconception

Another key fallacy is that of “justificationism”—the misconception that in order for knowledge to be valid, it must be “justified” by some authoritative source. But this begs the question… what is this ultimate source of truth? A leader? A religious text? An institution? Nature itself?

For much of human history, we relied on authority figures to tell us what was true and right, based on the presumed wisdom of the leaders of our tribe, government, church, etc. Their supposedly infinite knowledge conferred us feelings of certainty and social status.

The break away from this authoritarian tradition began with the boldness of ancient philosophers such as Aristotle, but truly accelerated in the 16th and 17th centuries with revolutionary thinkers such as Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, and Francis Bacon. These leaders helped shape the “Enlightenment,” an intellectual movement that advocated for individual liberty, religious tolerance, and a rebellion against authority with regard to knowledge.

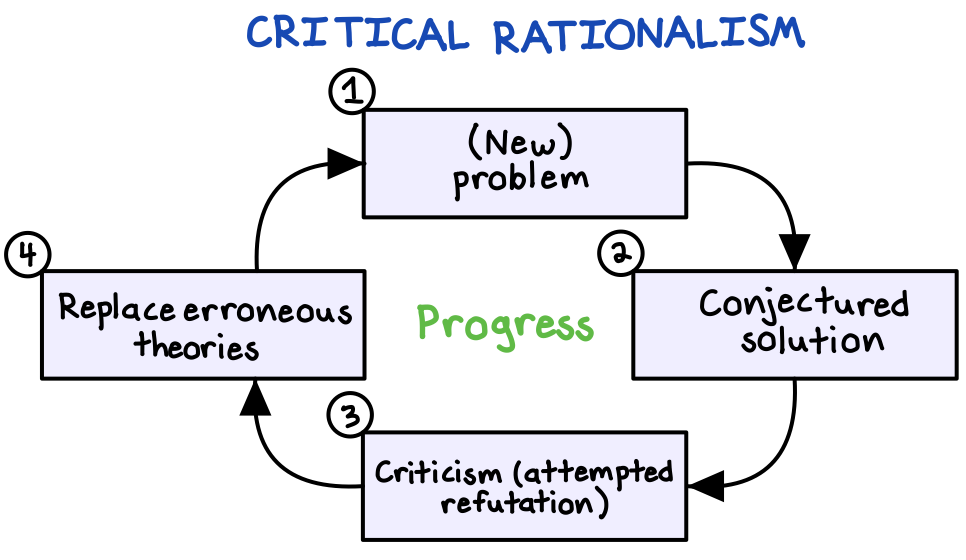

The reigning theory of how knowledge progresses

Standing on the shoulders of the Enlightenment giants, a 20th-century Austrian philosopher named Karl Popper—a towering thinker who nonetheless remains under-appreciated by the general public—transformed our understanding of the growth of knowledge with his theory of critical rationalism.

Popper’s theory advocated for the opposite of justificationism, called “fallibilism,” which recognized that while there are many sources of knowledge, no source has authority to justify any theory as being absolutely true. Tracing all knowledge back to its ultimate source is an impossible task, because this leads to an infinite regress (“But how do we know that source is justified?”).

Instead of asking, “What are the best sources of knowledge?”, Popper recommended that we ask, “How can we hope to detect and eliminate error?”3

“What we should do, I suggest, is to give up the idea of ultimate sources of knowledge, and admit that all knowledge is human; that it is mixed with our errors, our prejudices, our dreams, and our hopes; that all we can do is grope for the truth even though it may be beyond our reach.”

Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations (1963, pg. 39)

Popper acknowledged the inherent asymmetry between the justification of a theory and the refutation of one. Whereas it is impossible to definitively prove theories to be correct, we are sometimes able to prove them wrong. Let’s return to our extrapolating chicken. No matter how many days she observed that the farmer came by to feed her, she would never be able to definitively justify her “benevolent farmer” theory. But the one day that the farmer wrung her neck definitively refutes her theory. Sorry, chicken…

Error-correction, not ultimate truth

With this understanding, we arrive at the way in which knowledge actually progresses: through a problem-solving process of conjecture and refutation, also known as trial-and-error.

This process resembles that of biological evolution, in which nature “selects” for the random genetic mutations that are most successful at causing their own replication.4 Ideas, too, are subject to variation and selection.

Knowledge creation begins with creative conjectures—unjustified guesses or hypotheses that offer tentative solutions to our problems. We then subject our guesses to criticism, by attempting to refute them. We eliminate those that are refuted. We tentatively preserve the rest, but they can never be positively justified or proved. The only logically justified statements are tautologies—such as, “All people are people”—which assert nothing.

It is not “ultimate truth” that we are after, for even if such a thing did exist, there is no source that can verify it as unquestionably true. Our sense organs themselves are highly fallible. The best we can do is use our creativity to propose new guesses, then subject our best guesses to critical tests and discussion, using logic and the scientific method. When our tests successfully refute a theory, we abandon it. If we discard an old theory in favor of a newly proposed one, we tentatively deem our problem-solving process to have made progress.5

Einstein was right that he was wrong

It is easy to overlook how recent (relatively speaking) it was that science started to embrace the fallibility of all its theories. For this, we have Albert Einstein to thank.

For the 200+ years before Einstein, Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity had unprecedented experimental success; it was widely regarded as the “authoritative” theory of gravity. That is, until Einstein’s theory of general relativity (1915) destroyed the authority of Newton’s theory by showing that it was, in fact, merely a flawed approximation.

To this day, general relativity reigns as the dominant theory of gravity and spacetime, but Einstein himself was clear from the beginning that his theory was essentially conjectural. He did not regard general relativity as “true,” but merely as being a better approximation to the truth than Newton’s theory! We should take note that one of the greatest thinkers in history understood that his own revolutionary theory would inevitably be replaced.6

***

The overarching lesson is that everything is tentative, all knowledge is conjectural, and any good solution may also contain some error. Far from being a pessimistic view, Popper’s theory provides the very foundation for progress: error-correction.

We obtain the fittest available theory not by the justification of some unattainably perfect theory, nor by induction from repeated observations, but through the systematic removal of errors from our theories and the elimination of those which are less fit. Only a very few theories succeed, for a time, in a competitive struggle for survival.7

Notes

- Deutsch, D. (1997). The Fabric of Reality. Penguin Books. 59-62.

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The Beginning of Infinity. Penguin Books. 5-6.

- Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge & Kegan Paul. 32-36.

- Popper, K. (1994). The Myth of the Framework. Routledge. 2-7.

- Deutsch, D. (1997). 64.

- Popper, K. (1994). 91-92.

- Popper, K. (1963). 124-129.