“I’m all for fixing social problems … What I’m against is being very confident and feeling that you know, for sure, that your particular intervention will do more good than harm, given that you’re dealing with highly complex systems wherein everything is interacting with everything else.”

Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie’s Almanack (2006, pg. 253)

Complex systems are collections of simpler components—such as employees, money, or particles—that are interconnected in such a way that they “feed back” onto themselves to create their own complex patterns of behavior. Every person, organization, animal, plant, pond, country, or economy is a complex system. Their interconnections are called “feedback loops,” circular relationships through which one component affects another and is in turn affected by it.1

Feedback dynamics demonstrate how a system can generate collective (or “emergent”) behaviors that cannot be predicted by only observing the parts. We cannot study one employee (or one team, or one division) and determine everything that will happen in a large organization. Nor can we deduce the behavior of a person from a single brain cell. Nor that of an economy from a single economic policy.

The danger of ignoring feedback

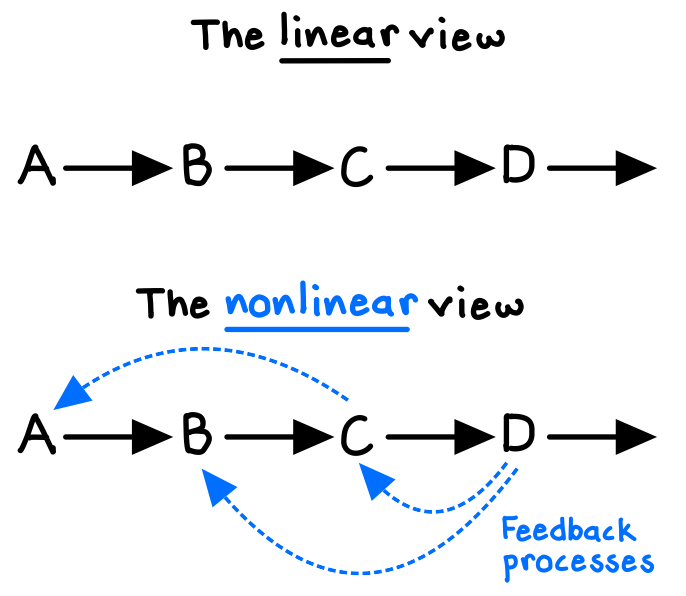

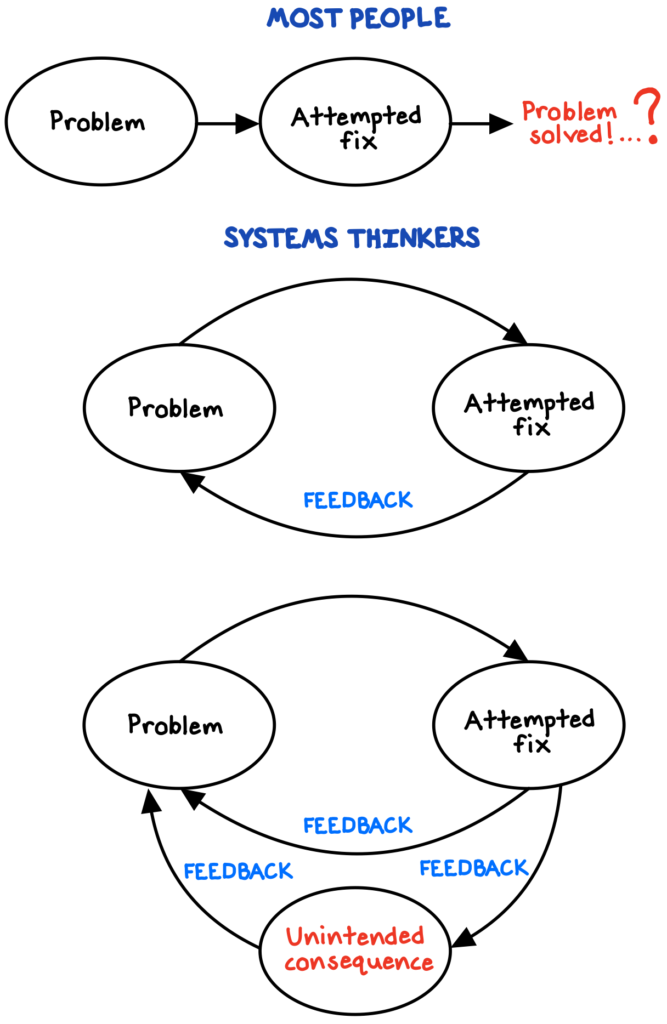

In life, we naturally gravitate towards simpler explanations, those that stem from the most coherent story we can tell from the information most readily available to us. It is much easier for us to craft a narrative where everything happens in isolation, a linear form of reasoning which sees the world as a series of sequential, cause-effect events. However, our world is complex; its relationships are often nonlinear. Ignoring feedback leads us to adopt blunt and short-sighted solutions to problems of complex systems.

Unanticipated feedback processes can help explain why economic policies rarely work as intended, why pest control efforts sometimes create entirely new pests, and why well-intentioned laws can backfire. In business, it is easy for decision makers to ignore or underrate feedback processes that could potentially undermine their strategies. Competitors, employees, suppliers, customers, lawmakers, and the media—each with their own interests—may all react or retaliate in unintended ways to a new business strategy or policy. Those reactions will trigger additional reactions, which will trigger additional reactions.

How can we disentangle the complexity?

With greater knowledge of the dynamics of both types of feedback loops (positive and negative) and how to analyze them, we can better understand the complex world we live in and use their power to create outsized change.

Equilibrium or explosion

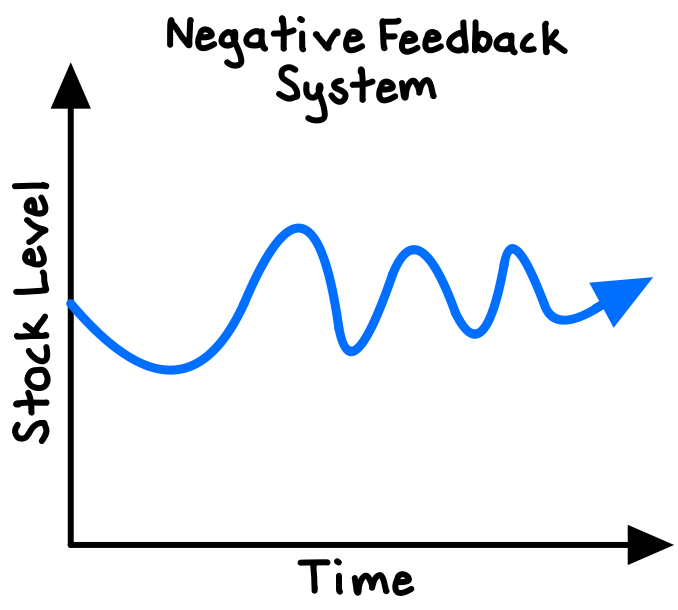

Negative (balancing) feedback loops are stabilizing, goal-seeking loops which aim to regulate the stock around a given level or range—to maintain a dynamic equilibrium. Consider how a thermostat constantly adjusts to maintain the temperature of the room at the desired setting.

In biology, balancing feedback manifests in all life forms through homeostatic behavior. For instance, to regulate body temperature, our bodies induce perspiration when they get too hot and shivering when they get too cold.

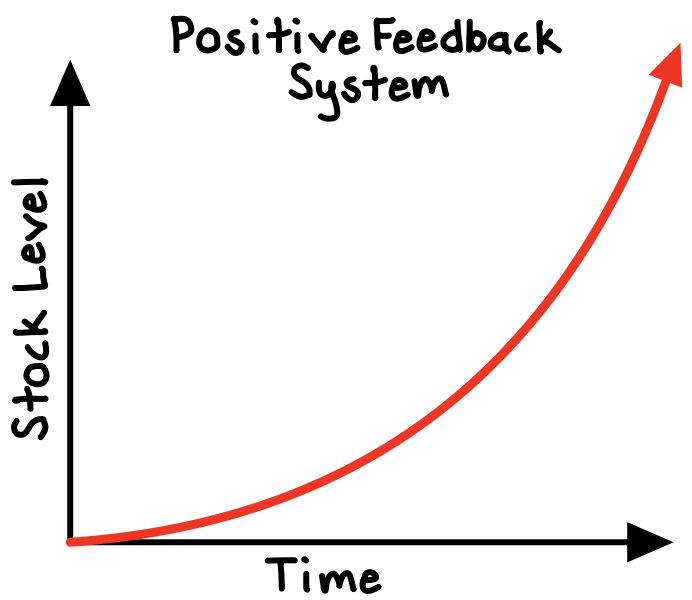

In contrast, positive (reinforcing) feedback loops are amplifying, self-multiplying loops which create either virtuous cycles of growth or vicious cycles of snowballing decline. These forces exist wherever a system element is able to grow (or shrink) as a constant fraction of itself, generating exponential growth (or exponential decay).2 Examples include a contagious virus, population growth, compound interest, economic growth, and network effects on social platforms such as TikTok.

Booms and busts

The economy provides a great example, as the “boom” and “bust” cycles that we observe occur largely due to reinforcing feedback loops running amok in the short-term, with balancing feedback loops kicking in to help reestablish long-term stability.

In the short-term, unsustainable “bubbles” can emerge from many reinforcing feedback loops fueling one another, such as high consumer and business confidence, excessive greed and speculation, low interest rates, and increasing asset prices. Similarly, bubbles can “pop” due to reinforcing feedback loops that accumulate into a self-perpetuating downward cycle. For instance, an external shock (such as a pandemic or a war) might trigger fear, leading to reduced confidence and business contraction, leading to market sell-offs, leading to more fear, and so on.

Fortunately, negative (balancing) feedback mechanisms help stabilize and regulate the economy. The free movement of prices is a negative feedback loop that helps nudge supply and demand toward equilibrium. For example, rapidly rising home prices will eventually shut out many potential buyers. The Federal Reserve wields negative-feedback tools, such as raising or cutting interest rates and increasing or reducing the money supply, designed specifically to help cool a hot economy and ignite a weak one. Likewise, governments can hike or cut tax rates and increase or decrease fiscal spending.

Given all these feedback dynamics, the difficulty of accurately predicting the economy is unsurprising. Countless institutions and individuals are entangled in a complex web of reactions and fluctuations. But we can see how a complex system such as the economy, through its interconnected feedback loops, can essentially “self-organize” into long-term stability, despite periods of short-term turbulence.3

Mappin’ systems, smokin’ doobies

We tend to operate as if we know for certain what implications our actions will have. But without a complete picture of the feedback dynamics at play, we cannot fully understand if our chosen intervention is the best one, or if it will do more harm than good.

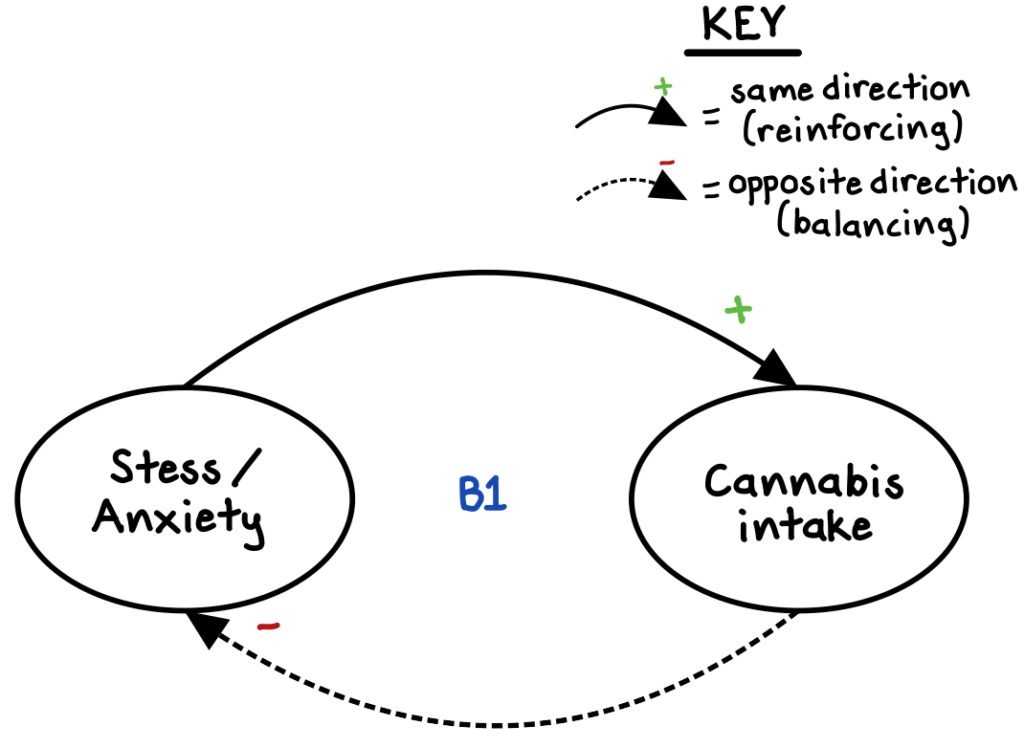

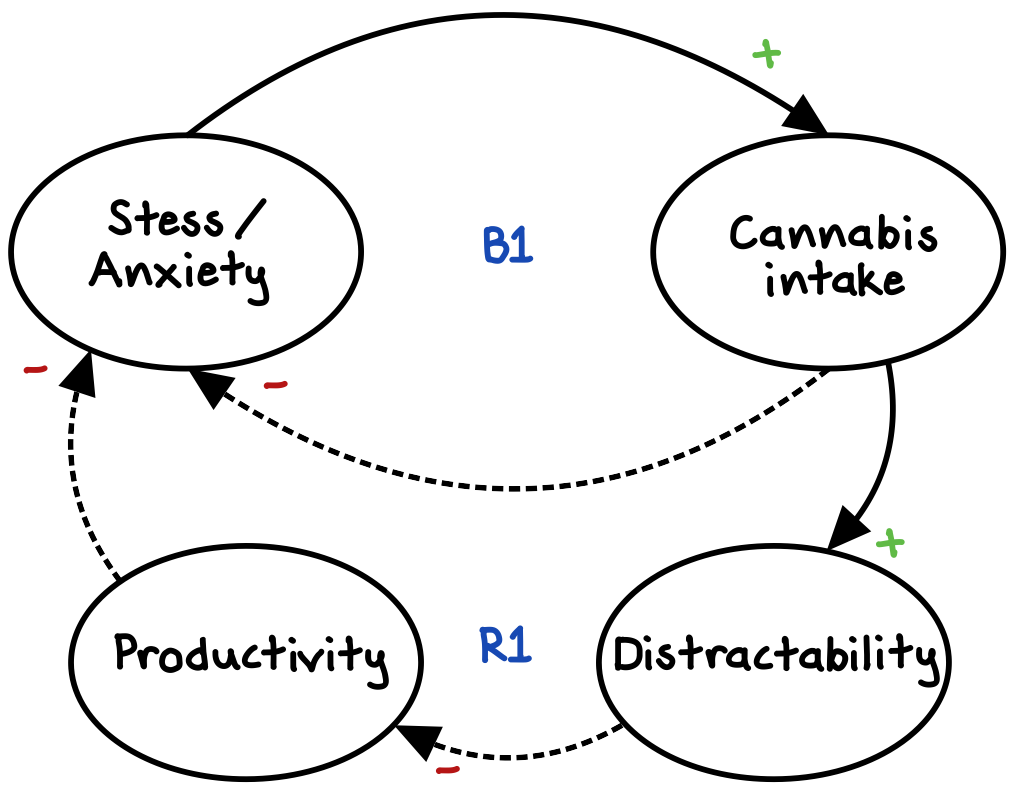

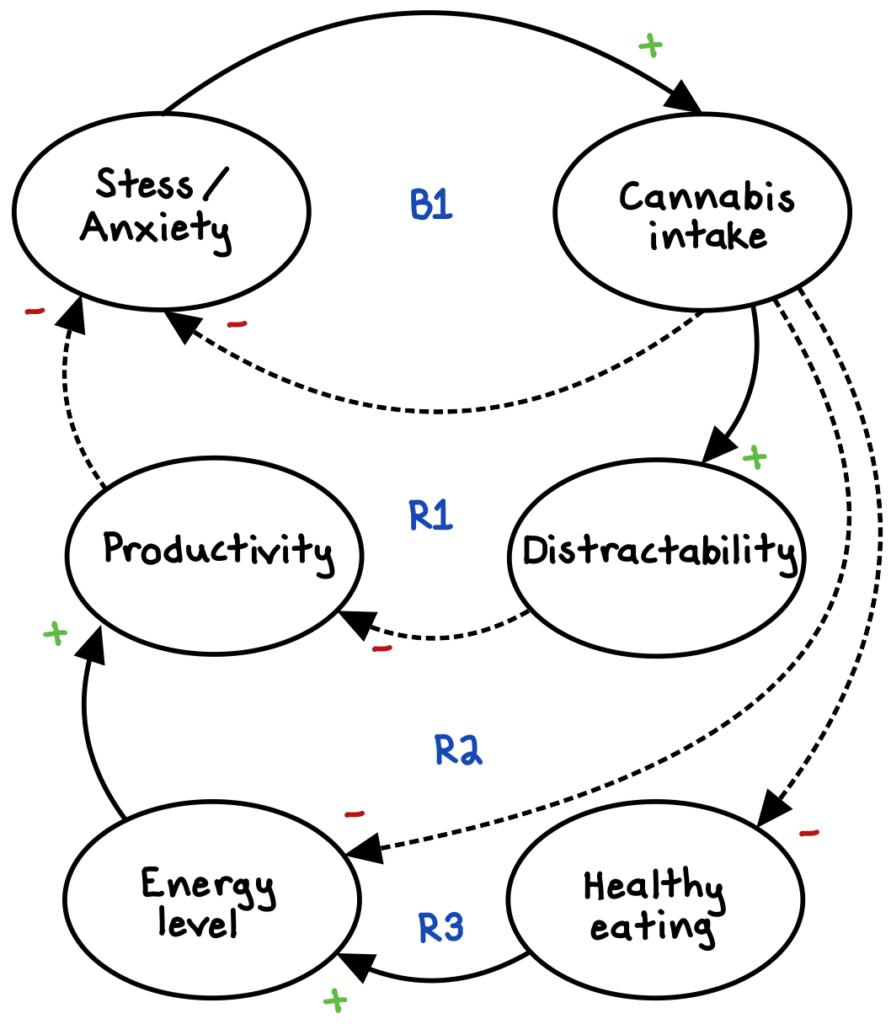

Fortunately, we can map it out. Systems mapping is an invaluable, iterative exercise in which we create a causal loop diagram of the feedback processes at work in the system of interest, including the direction of the feedback and an indication of whether that feedback is reinforcing or balancing. This process can help uncover how feedback is generating behavior that we want to change, and how to anticipate potential side effects.4

Let’s try it out. Say we are a busy person and that high stress is a recurring problem. To ease our anxiety, we try using some cannabis. This is a balancing loop, since higher marijuana use temporarily reduces our stress level.

If we stop our analysis here, increasing our cannabis intake seems effective. But let’s put down the bong and keep going. Cannabis also increases how easily we are distracted. More distraction means lower productivity, which increases the anxiety we were trying to alleviate in the first place.

Cannabis also temporarily reduces our energy level, exacerbating our productivity loss, and might make us more prone to unhealthy eating, further reducing our energy level and harming our productivity.

This logic could go on and on, but it demonstrates how the process of systems mapping can help unearth potential unintended consequences that could exacerbate, rather than cure, our original problem. This process can empower decision makers to avoid problems before they actually emerge.

***

The key lesson is that changing one variable in a system can affect other variables and even other systems. We must consider system elements not just in and of themselves, but in relation to the system as a whole and to the greater environment.

When faced with a complex decision, good strategists should pause and map it out.5 As we work iteratively through the systems mapping process, we can:

- Identify the critical system elements and the feedback loops between them;

- Given those relationships, evaluate whether a given approach is likely to actually produce the intended outcome;

- Consider how to enhance or moderate these forces to achieve better outcomes;

- Question whether, over time, other feedback effects could kick in to challenge or even reverse any short-term successes; and,

- Determine whether the potential for unwanted side effects outweighs the benefits.

By approaching decisions through the lens of feedback dynamics, we will have an incredible competitive advantage over others!

Notes

- Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2.

- Meadows, D. (2008). 30-34.

- Gribbin, J. (2004). Deep Simplicity. Random House. 160-161.

- Kim, D. (1999). Introduction to Systems Thinking. Pegasus Communications. 12-16.

- For a great guide, see: Guidelines for Drawing Causal Loop Diagrams. (February 2011). The Systems Thinker, 22(1), 5-7.