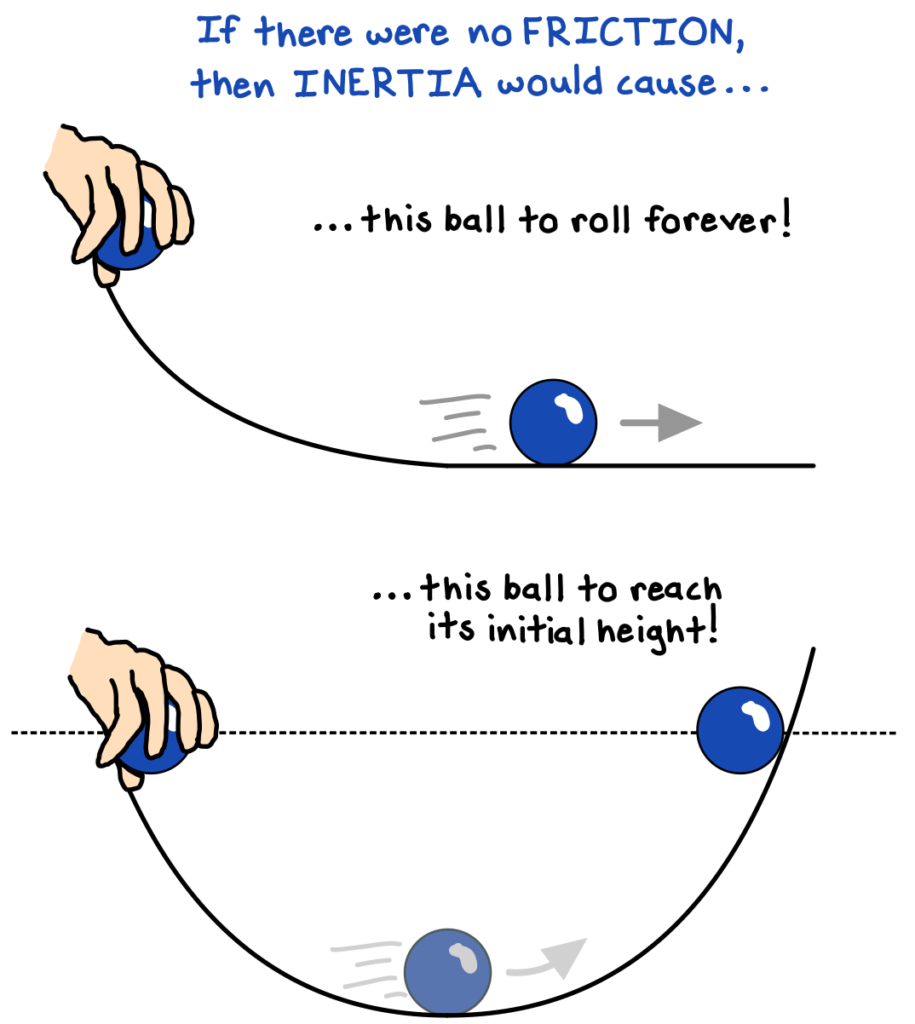

If an object is left alone, if no other force (such as friction) acts upon it, it will maintain its current state of motion. Objects already in motion will continue to move forward with a constant velocity, and stationary objects will continue to stand still—unless another force intervenes.1 The more massive the object, the greater the tendency to resist changes in its motion.

The principle of inertia is a fundamental physical rule of motion, first discovered by Galileo and later codified as Isaac Newton’s “First Law” of gravity.

More broadly, we can observe inertia effects in the behavior of individuals, systems, organizations, and relationships. Whether obviously or subtly, effects of inertia are pervasive, and leveraging their power can be an effective strategic tool.

Stasis: the easier way forward

Correcting or reversing our current course is costly and effortful. The status quo is easier. Following the forces of inertia allows us to minimize the use of energy, but it can also lead us towards stagnation and decay as the environment shifts beneath our feet.

Consider how we tend to succumb to inertia by continuing to use obsolete technology standards even after new, better technologies have been introduced. For example, the original “QWERTY” keyboard layout has persisted for more than a century, primarily because people have simply become accustomed to it. QWERTY endures despite the fact that an alternative system called the “Dvorak” layout enables more than double the share of keystrokes to be done in the home row and requires about 37% less finger motion than QWERTY.2 Dvorak was too late; inertia prevails.

Recognizing inertia and either combating it or capitalizing on it can be a very productive endeavor, especially in competitive systems such as business, where adaptability and dynamism are key.

Expunging (or exploiting) inertia in business

“There is nothing more difficult… than to take the lead in the introduction of change. Because the innovator has for enemies all those who have done well under the old conditions and lukewarm defenders in those who may benefit under the new.”

Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince (1532)

In organizations (especially larger ones), inertia ensures that change is difficult. Because people generally fear uncertainty and prefer the status quo, they tend to resist new norms or strategies that undermine their existing responsibilities and routines.

As with resisting the forces of entropy (the universal tendency towards disorder in the physical world), combating inertia requires an outside energy injection.

Let’s consider four key types of inertia in business, each of which can present a threat or a strategic opportunity.

1. Routine inertia

Inertia can live in obsolete or inefficient routines, such as excessively large meetings or complex approval processes. These behaviors are often addressable by retraining or replacing managers who have invested many years in developing and applying the obsolete processes, as well as by reorganizing business units around new patterns of information flow. The routines that worked in the past may be wildly inappropriate for future contexts.3

2. Cultural inertia

Moreover, long-established cultural behaviors can prevent companies from promptly responding to competitive threats. Breaking cultural inertia demands simplification to eliminate the hidden inefficiencies buried beneath complex behaviors and back-door bargains between teams. Simplification may demand eliminating excessive administration functions, non-core operations, coordinating committees, or complex initiatives. It may require breaking up entire organizational units, or even reorienting the company entirely towards a redefined strategy.4

For example, in 2021, Volkswagen—then the world’s largest carmaker—had outspent all rivals in a race to beat Tesla in the development of electric vehicles. Volkswagen attributed its struggles to make an attractive electric vehicle in part to the failure of company’s managers, lulled into complacency by years of high profitability, to recognize that electric vehicles are more about software than hardware. The culture and competencies that enabled them to produce exquisitely engineered gas vehicles did not translate into coding prowess. The company’s CEO eventually acknowledged, “VW must completely change.”5 He was right.

3. Customers’ inertia

Consumers themselves also exhibit inertia by generally following their past behaviors. For example, we tend to keep the same bank accounts and to auto-renew our insurance policies and subscriptions—generally without conscious choice.6

The big banks know this, and make massive profits as a result. One analysis estimated that U.S. savers missed out on more than $600bn in interest payments from 2014-22 by keeping their savings in the five biggest banks instead of in higher-yield money-market accounts that paid over 10x higher interest rates.7 The giants are banking on inertia: that their customers are unlikely to investigate the alternatives and migrate their accounts to other banks, so there’s no need to offer competitive interest rates.

4. Competitors’ inertia

Business strategist Hamilton Helmer coined the term “counter-positioning” to describe the strategy in which a new entrant adopts a novel business model that would be irrational for an incumbent to mimic (capitalizing on their inertia). If copying a new product or technology would mean undermining their legacy profit streams, incumbents may calculate that inertia is preferable.

For example, around 2000, Netflix pioneered the mail-order DVD business based on the key assumption that Blockbuster, the then-dominant brick-and-mortar DVD rental giant, would be slow to recognize and respond to the threat of Netflix’s new model, allowing Netflix to steal away their customers who were tired of paying $1/day late fees.8 Eventually in 2004, Blockbuster did launch its own DVD subscription service, Blockbuster Online—but it was too late. The costly launch exacerbated Blockbuster’s financial distress. In desperation, Blockbuster actually pivoted back to its brick-and-mortar business.9 By 2010, Blockbuster had filed for bankruptcy, while Netflix went on to become one of the century’s best-performing stocks.

***

In general, the principle of inertia reminds us to be intentional, and to avoid complacency. Deciding not to make a change is making a decision—to preserve the status quo. But what we did in the past may or may not have been optimal at the time, and may be entirely suboptimal in the future. We must be vigilant in reviewing the choices—conscious or otherwise—that we make to keep things as they are to ensure we are adapting appropriately as the complex systems we live in shift beneath our feet.

Notes

- Feynman, R., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (2010). The Feynman Lectures on Physics (3rd ed., Vol. I). Basic Books. 9-1.

- Liebowitz, S., & Margolis, S. E. (1990). The Fable of the Keys. The Journal of Law and Economics, 33.

- Rumelt, R. (2011). Good Strategy/Bad Strategy. Crown Business. 203-208.

- Rumelt, R. (2011). 208-212.

- Boston, W. (2021, January 19). How Volkswagen’s $50 Billion Plan to Beat Tesla Short-Cirtuited. The Wall Street Journal.

- Rumelt, R. (2011). 212-214.

- Rabouin, D. (2022, December 8). The $42 Billion Question: Why Aren’t Americans Ditching Big Banks?. The Wall Street Journal.

- Helmer, H. (2016). 7 Powers. Deep Strategy LLC. 19-20.

- Huddleston Jr., T. (2020, September 22). Netflix didn’t kill Blockbuster — how Netflix almost lost the movie rental wars. CNBC.