Leverage points are places within a complex system—such as a corporation, an economy, a city, or an ecosystem—in which a small shift in input force can produce amplified changes in output force.1 When concentrated towards the most critical areas for improvements, even small shifts in our efforts can cause large, durable changes.

If we care about maximizing our impact in our companies, communities, or personal lives, leverage is one of the most valuable models to understand.

Taking the systems perspective

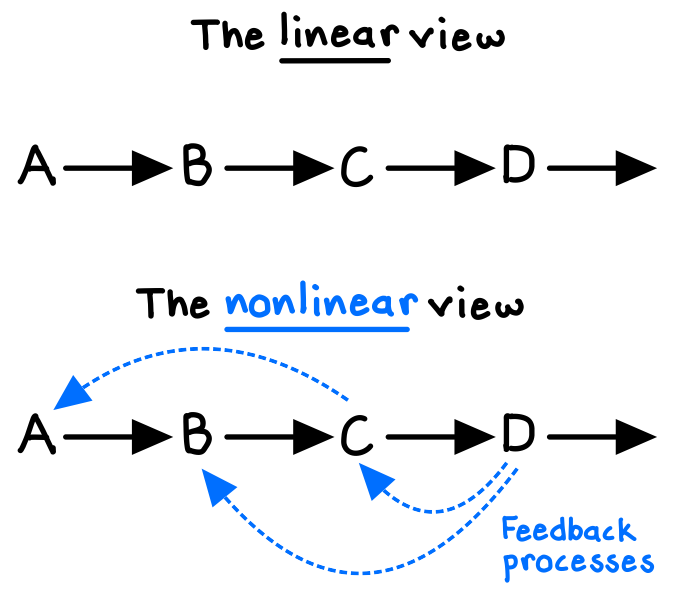

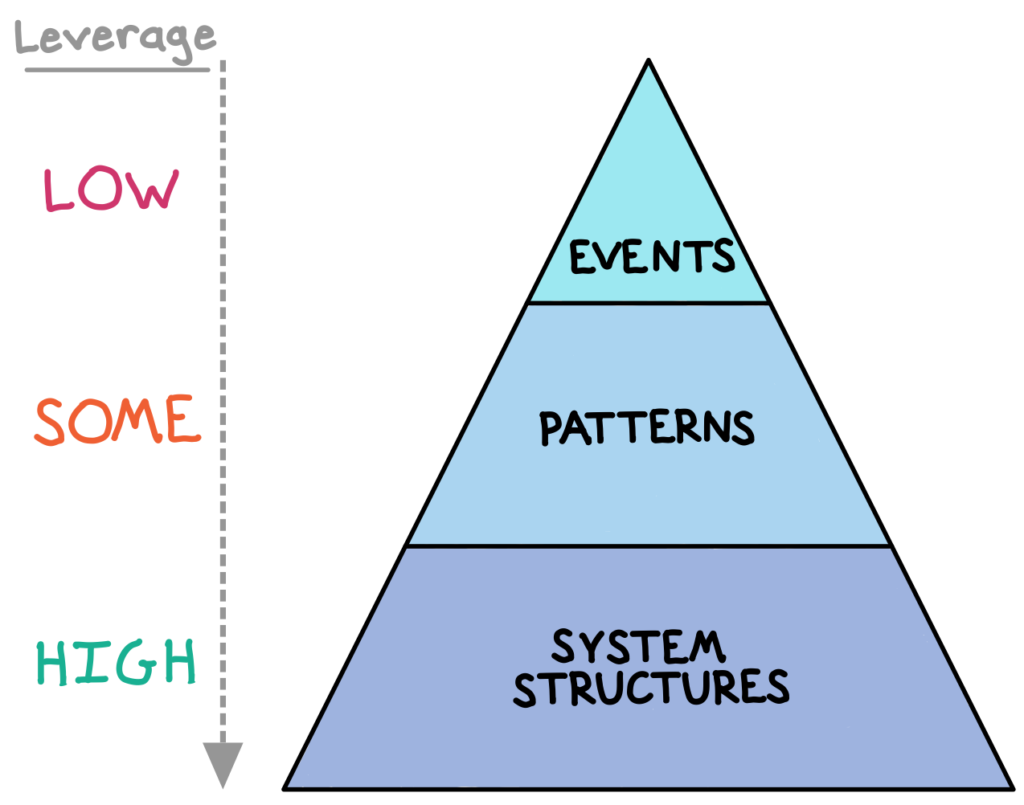

Unfortunately, we live in an event-oriented society, in which we focus mainly on our day-to-day experiences. Things happen, we react, then we repeat tomorrow. Reacting to events is the lowest-leverage way to instigate change. It oversimplifies the world into a series of linear, cause-effect events, while ignoring the deeper causes underlying our experiences. In reality, our world is a web of interwoven relationships and feedback loops.

Consider complex societal problems such as homelessness or income inequality. Seemingly plausible solutions to these issues can produce highly unpredictable results and unwanted side effects.

Adopting a systems perspective, on the other hand, allows us to unearth the highest-leverage places for intervention. By looking beyond individual events and studying the higher-level patterns of behavior of the system, we can identify and act on the system structures creating those patterns.2

Tackling homelessness

Consider the problem of homelessness. In order for individuals to qualify for permanent housing support, traditional policies have required homeless people to address certain issues that may have led to the episode of homelessness—for example, by requiring negative drug tests or mental health treatments.

These contingencies often lead to affected individuals getting entangled in bureaucracy and trapped in a vicious cycle where becoming homeless actually exacerbates the issues that caused the episode in the first place, such as unemployment, substance abuse, or medical issues—making it harder and harder to overcome. Simply put, these are low-leverage solutions.

However, modern policies have begun to adopt so-called “Housing First” principles, which enact a simple rule: offer basic permanent housing as quickly as possible to homeless people, followed by additional supportive services. Early research suggests that Housing First policies have helped improve housing stability, reduce criminal re-convictions, and decrease ER visits—all while saving money.3 That is leverage.

The leverage points checklist

Leverage points are not always intuitive, and are ripe for misuse. The checklist below provides a useful aid to identifying them (ordered from least to most impactful):1,4

9. 🔢 Number & Parameters

Sadly, the majority of our attention goes to numbers, such as tax rates, revenue goals, subsidies, budget deficits, or minimum wage. Typically, they don’t provide much leverage on their own, because they rarely change behavior. Truly high-leverage parameters, such as interest rates, are much more rare than they seem.

8. 🏗 Physical Interventions

Physical structures that are poorly designed or outdated can be potential leverage points, but changing them tends to be difficult and slow relative to other, “intangible” interventions.

7. 🔁 Balancing (Negative) Feedback Loops

Negative feedback mechanisms can help systems adjust towards equilibrium, such as how the Federal Reserve adjusts interest rates to promote economic stability, or how companies use employee performance reviews to highlight growth areas and take corrective action if needed. Affecting the strength of these balancing forces can create leverage by reigning in other forces.

6. 📈 Reinforcing (Positive) Feedback Loops

Positive feedback mechanisms can fuel virtuous growth cycles (as with compound interest on an investment portfolio), but left unchecked they will create problems (such as exploding inequality).

Weakening reinforcing loops usually provides more leverage than strengthening balancing loops. For example, the “Housing First” policies discussed above aim to obviate the self-perpetuating nature of homelessness before the loop begins by simply giving people housing immediately.

5. 📲 Information Flows

Simply by improving the efficiency with which useful information can feed back to decision makers, we can often create tons of leverage by enabling better and more timely decisions. Poor quality or slow information can undermine individuals and organizations of all kinds.

4. 📜 Rules

Whoever controls the “carrots and sticks” in a system can exert massive influence. A country’s constitution, a legal system, and a company’s employee compensation plan are all potential high-leverage rules.

For example, salespeople traditionally receive a commission for every deal they close. These schemes provide strong incentives to do big deals and as many as possible. Recognizing that these incentives can fail to promote good post-sale customer support and breed unhealthy internal competition, some executives are experimenting with “vested commissions,” which are paid out over time to sales and customer success employees alike. Such rules can help foster a culture based on relationships and long-term customer success, rather than on transactions.5

3. 👩🏽🔬 Experimentation

Evolutionary forces are remarkably powerful, even outside of nature, where genetic variation and selection enables species to develop incredible adaptations. Similarly, companies or countries that are able to innovate and evolve will become more adaptable and resilient.

A culture of experimentation helps explain the success of Google, Amazon, and many others. Many firms fail to innovate simply due to an intolerance for failure. The vast majority of experiments will flop; the challenge is in viewing those failures as opportunities for improvement and learning instead of as wasteful side projects.6

2. 🎯 Goals

Every system has a goal, though not always an obvious one. All companies, viruses, and populations share the goal to grow—a goal which becomes dangerous if left unchecked. Change the goal, and you change potentially everything about the system.

1. 💡 Ideas

Our shared ideas (or “mental models”) provide the foundation upon which we interpret all our experiences. These ideas may be deeply embedded, but there is nothing inherently expensive or slow about changing them. For high-leverage impact, we must be willing to challenge existing ideas. Step back, take an outsider perspective, expose the hidden assumptions in our ideas, and reveal their weaknesses or contradictions.

Remember: all knowledge is tentative and conjectural. As with Einstein supplanting Newton, our best theories can be toppled at any time by newer, better ones. Since the world is always capable of surprising us, the best approach is to keep our minds open!

Private equity, lords of leverage

The business world offers great real-world applications of leverage, notably in the private equity (“PE”) industry, whose whole operating model revolves around applying principles of leverage.

PE firms seek to buy-out underperforming companies, turn them around, and sell them for a large profit. They immediately identify and act on key system intervention points. For instance, they promptly change the goal of the companies: generate more cash flow. By stressing 2-3 success levers and concentrating efforts towards them, they instigate reinforcing feedback loops. They use debt, which not only amplifies financial returns but also acts as a balancing loop by instilling cash-flow discipline on management. Finally, they often change shared ideas by replacing prominent executives.7

The success of this systematic approach is well-established. A 2020 study found that US buyout funds have outperformed the public stock market in nearly every year since 1991.8

***

While PE is just one example, the overarching lesson across economic, social, and political systems is that we can drastically increase our impact if we pause, adopt a systems-level view, and assess what points of intervention will most effectively push us towards our goals.

Notes

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. The Sustainability Institute.

- Kim, D. (1999). Introduction to Systems Thinking. Pegasus Communications. 17-18.

- Data Visualization: The Evidence on Housing First (2021, May 25). National Alliance to End Homelessness.

- Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing. 145-165.

- Fadell, T. (2022). Build. HarperCollins. 292-299.

- Thomke, S. (2020). Building a Culture of Experimentation. Harvard Business Review, R2002B.

- Rogers, P., Holland, T., & Haas, D. (2002). Value Acceleration: Lessons from Private-Equity Masters. Harvard Business Review, R0206F.

- Cembalest, M. (2021). Food Fight: An update on private equity performance vs. public equity markets. JP Morgan Asset and Wealth Management. 4-8.