“(T)here is no fundamental barrier, no law of nature or supernatural decree, preventing progress. Whenever we try to improve things and fail, it is… always because we did not know enough, in time.”

David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity (2011, pg. 212)

In today’s news and social media environment, optimism is scarce. We are constantly bombarded with claims that society is heading in the wrong direction, that our children will be worse off, that some problem or trend will ensure our demise. These pessimistic messages poison the conversation around a variety of threats: climate change, artificial intelligence (AI), nuclear apocalypse, extraterrestrial invaders, etc.

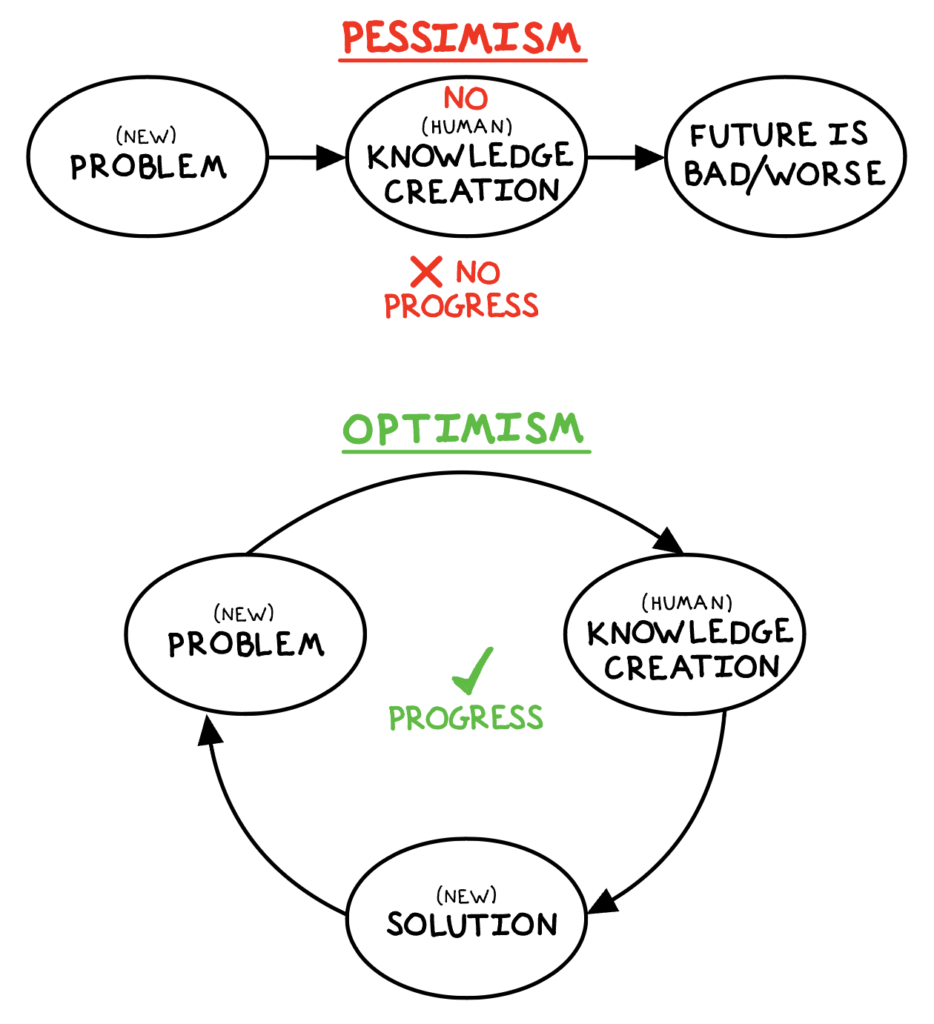

It’s true that problems are inevitable. It’s also true that there’s no guarantee we will solve these problems. However, we frequently behave (often unknowingly) as if we are not capable of solving them. The truth is that we humans have the gift of creating new knowledge. The future is never doomed to tragedy nor destined to bliss, because the knowledge that will determine the future has not yet been created.

Pessimism is self-enforcing. The (implicit) assumption that we can’t or won’t create the knowledge to solve our problems discourages us from even trying. On the other hand, optimism, the belief that we are capable of solving problems, is not merely a more pleasant way to approach life; in fact, it is the more rational approach to the future.

The futility of pessimism and prophesy

Pessimism is an ancient plague. Indeed, in the Biblical book of Ecclesiastes, King Solomon lamented the futility of life and knowledge:

“For with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief.”

Ecclesiastes 1:18

Many ancient philosophers and modern thinkers have echoed the king’s dread. Sure, ignorance may be blissful for some, but King Solomon had it backwards: the creation of knowledge is the only way to eliminate the world’s sorrows.

The famous population theorist Thomas Malthus offers a great example. In 1798, Malthus built a model of population growth and agricultural growth which led him to prophesy that excessive population growth destined humanity to mass famine, drought, and war in the 19th century. He believed that the poor and uninformed procreated imprudently, that periodic checks on the birth rate were necessary, and that people were unlikely to behave as required to avert these disasters.1 Malthus and other prominent thinkers believed he had discovered the end of human progress.

Malthus’s population growth predictions were actually fairly accurate. However, his prophesied dooms never materialized. Instead, the food supply grew at an unprecedented rate in the 19th century due to remarkable innovations such as plows, tractors, combine harvesters, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides.2 Living standards rose considerably. Today, the number of humans is 10x larger than in Malthus’s time, yet famine mortality rates have plummeted.

The principle of optimism

The mistake Malthus made remains common today: failure to account for the potential for humans to create new knowledge, new technology. Whenever we make predictions of the future but ignore this key factor, we inevitably devolve into pessimism—and our predictions become prophecies.

The brilliant physicist David Deutsch offers a prescription, a worldview he calls the “principle of optimism”:

“All evils are caused by insufficient knowledge.”

David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity (2011, pgs. 212-213)

By “evils,” Deutsch is not referring to Hitler or Thanos; he is referring to unsolved problems. He argues convincingly that the only permanent barriers to solving problems are the immutable laws of physics. As long as a solution does not require breaking these laws (for example, if it required traveling faster than the speed of light), then humans have the potential to create the knowledge needed to solve any problem, given time.3 Fortunately, creating new knowledge is a distinctive human specialty.

AI doomsday?

Let’s consider one of the most common areas of pessimism today: AI. Over the years, many renowned thinkers—from Alan Turing to Elon Musk—have proposed various doomsday theories that AI will make humans obsolete or, worse, conquer and enslave them.

Aaron Levie, Founder/CEO of Box, offered a thought-provoking counter-argument to the common assertion that AI will simply replace human workers in droves. Consider the claim that if AI could make a company 50% more profitable in a given function, it would also eliminate 50% of workers in that function. Levie rightly criticizes these naively pessimistic arguments:4

- First, AI-displacement claims assume that companies are already operating with the maximum amount of labor they would or should have, if budget weren’t a constraint. In reality, companies may prefer to utilize the efficiency gains from AI to scale-up their operations, which might involve hiring more humans—not fewer. New business growth may promote even more investment.

- Second, AI-displacement claims ignore the probability that competitors will also act in response to productivity gains, pressuring other firms to increase their own productivity—even at the expense of profits. Competition may demand they retain, or even expand, their workforces.

Levie is right. These AI-displacement arguments often ignore the second-order feedback effects that are characteristic of complex systems. We cannot simply assume that if AI leads to higher productivity, then humans will become obsolete. Rather, the impact of AI productivity gains on the demand for labor is unknowable, because the knowledge that humans will create in the future is unknowable. As with most new technologies, it’s likely that AI reduces the demand for labor in certain domains, increases it in others, and even opens up entirely new domains.

Most AI doomsday claims involve textbook pessimism: they implicitly assume that we will create no new knowledge and simply accept our fate—in other words, that progress is over. Instead of prophesying our eminent obsolescence, we would be better off testing and improving on new technologies, investigating how to deploy and control them responsibly, and learning how to adapt and reconfigure our societies to new circumstances. We have, in fact, made such evolutions countless times throughout history.

If AI does make humans redundant or conquer the world, it won’t be because we were incapable of solving the problem. The ultimate impact that AI has on humans is up to, well, humans.

A rational preference for the unknown

Pessimism also tends to emerge when we face decisions between the familiar and the unfamiliar. It’s quite easy to dismiss new ideas or possibilities simply because we’re more comfortable with the status quo.

A fascinating thought experiment from computer science offers a compelling case for why, under many conditions, we should actually prefer the unknown to the known—that is, why optimism can be rational.

In the “multi-armed bandit problem,” you enter a casino filled with slot machines, each with its own odds of paying off. Your goal: maximize total future profits. To do so, you must constantly balance between trying new machines (exploring) and cashing in on the most promising machines you’ve found (exploiting).

The problem has a fascinating solution, the “Gittins index,” a measure of the potential reward from testing any given machine—even one we know nothing about.5 We should prefer a machine with an index of, say, 0.60 to one with 0.55. The only assumption required is that the next pull is worth some constant fraction of the current pull. Let’s say 90%.

Here’s the fascinating part: an arm with a record of 0-0 (a total mystery) has an “expected value” of 0.50 but a Gittins index of 0.703. The index tells us we should prefer the complete unknown to an arm that we know pays off 70% of the time! The mere possibility of the unknown arm being better boosts its value. In fact, a machine with a record of 0-1 still has a Gittins index over 0.50, suggesting we should give the one-time loser another shot.6

The Gittins index offers a formal rationale for preferring the unknown. Exploration itself has value for the simple reason that new things could be better, even if we don’t expect them to be.

This type of reasoning carries over to all “explore/exploit” decisions. For example, how should companies balance between milking their current profitable products today versus researching and developing new ones? Or, how should societies allocate resources between ensuring energy availability with traditional fossil fuels versus investing in low-carbon alternatives like solar or nuclear? The Gittins index illustrates that the mere potential for progress means that trying new things is often the rational approach to the future.

***

Rational optimism is not naïve: we aren’t guaranteed to solve our problems. We could fail or destroy ourselves. However, we should be endlessly encouraged by the fact that the universe does not preclude us from solving our problems! We have all the tools we need.

Progress emerges from learning and creating the right knowledge to address our problems, current and future. Assuming otherwise, or—equally dangerous—failing to remember that creative problem-solving is a human specialty, leads us inevitably to pessimism, prophesy, and error. As Winston Churchill explained about why he was an optimist, “It does not seem to be much use being anything else.”

Notes

- Durant, W. & Durant, A. (1968). The Lessons of History. Simon & Schuster. 21-22.

- Bellis, M. (February 6, 2021). American Farm Machinery and Technology Changes from 1776–1990. ThoughtCo.

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The Beginning of Infinity. Penguin Books. 212-216.

- Levie, A. [@levie]. (2024, April 6). One of the most common concerns about AI [Post]. X.

- Technically, the Gittins index completely solves the multi-armed bandit problem with geometrically discounted payoffs. However, the problem has no general solution.

- Christian, B., & Griffiths, T. (2016). Algorithms to Live By. Henry Holt and Co. 37-42.