One of the most foundational scientific concepts is the idea of realism, the common-sense view that there exists an objective physical reality independent of any individual’s own consciousness.1 But that doesn’t mean that everything appears the same to everyone; in fact, one of the deepest theories of physics tells us the exact opposite.

Albert Einstein’s groundbreaking theories of relativity demonstrated that time and distance are relative notions, and that they are really two parts of the same thing—a fourth dimension we refer to as “spacetime.” A point in spacetime, called an “event,” is both a location and a moment.

Einstein’s “special theory of relativity” (1905) challenged our intuitive understanding of time and space. According to relativity, observers moving at different speeds will get different answers when measuring lengths and durations.2 For instance, an observer who is moving quickly will experience time more slowly than one who is stationary. The watch of the moving observer would quite literally tick more slowly.3

In other words, time is relative. The only thing that remains fixed is the speed of light—around 186,000 miles per second in a vacuum.

The so-called “twin paradox” provides an incredible example of relative time. Imagine identical twin sisters together on Earth. If one twin hops in a rocket and flies directly away from Earth at a very high speed, while the other one remains stationary on Earth, when the spacefaring twin returns she will be younger than her sister on the ground!4

Even beyond physics, relativity as a concept teaches us that our everything depends on our individual vantage point, which rarely paints a complete picture.

Tricks of perspective

We experience relativity whenever we are riding in a car, train, or airplane. When we are traveling in smooth, linear motion at constant velocity, we will not perceive the speed of our movement without an external frame of reference (such as a window), whereas an outside observer could clearly observe this movement. This is also why we don’t “feel” the rotation of the Earth.

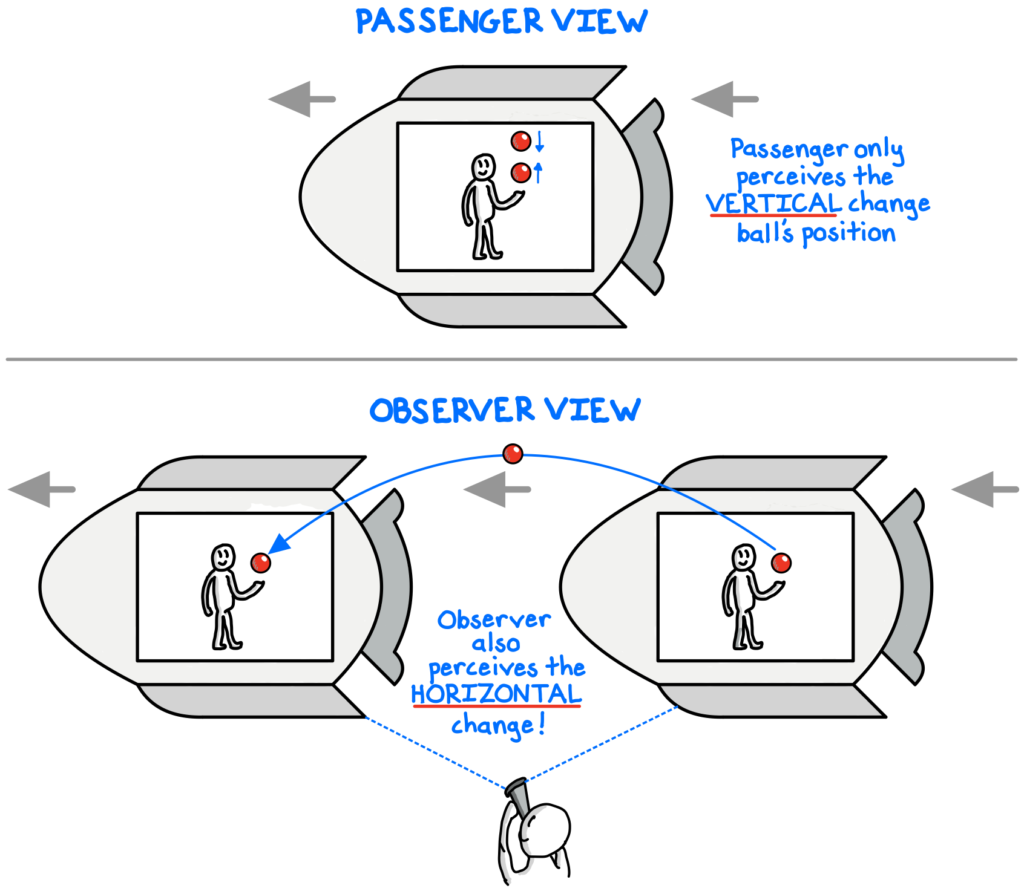

Suppose that you are a passenger on a rocket traveling at a uniform velocity and you toss a ball up in the air and then catch it. You will only perceive the vertical change in the ball’s position. Now suppose you are a stationary observer of the rocket passing by overhead (and you have special x-ray vision into the rocket). You will also notice the horizontal movement when the passenger tosses the ball as the rocket moves across your field of vision. The passenger will not notice this horizontal movement, because he and the ball are moving at the same velocity as the rocket!

Even the most beautiful theory is fallible

Observing that his theory of special relativity did not fit with Isaac Newton’s 200-year-old theory of gravity, Einstein printed another article in 1915 providing a complete solution: the “general theory of relativity,” one of the most powerful and elegant theories ever produced by mankind. This elegant theory posits that space can expand and contract, and that it curves in the presence of matter, such as planets or stars.5

Einstein’s groundbreaking theory transformed our understanding of physics and the universe, superseding Newton’s theory of mechanics and gravity that had dominated our thinking for centuries. This is perhaps the best example to remind us that every theory can be wrong. To this day, Newton’s predictions remain incredibly accurate for most practical circumstances; his theory was just incomplete.

“It was a shocking discovery, of course, that Newton’s laws were wrong, after all the years in which they seemed to be accurate. Of course it is clear, not that the experiments were wrong, but that they were done over only a limited range of velocities, so small that the relativistic effects would not have been evident.”

Richard Feynman, The Feynman Lectures on Physics (1963, Vol. I pgs. 16-1—16-2)

Despite its revolutionary impact, we already know that general relativity cannot be a complete description of reality. Although it explains the motions of larger objects (from planetary orbits to billiards ball trajectories) with great accuracy, it breaks down when describing the bizarre behaviors of microscopic particles. That realm belongs to quantum theory, the other pillar of physics, which—perplexingly—cannot explain gravity.

Fortunately, scientific knowledge progresses not by discovering unattainably perfect theories, but by the repeated toppling of our best theories by stronger, more testable, more unifying ones. We can simultaneously regard both general relativity and quantum theory as our best current explanations in their respective domains, and expect that both theories will be eventually be revised, unified, or replaced!

No single perspective rules

The concept of relativity holds profound implications beyond physics, particularly by underscoring the value of diverse perspectives in our everyday thinking and decision making, including in social systems such as organizations or governments.

Everything (except the speed of light) depends on one’s perspective; there is no “ruling” frame of reference. There is no single, shared “present” in the universe, only the appearance of such with the objects that are close to us and moving at similar speeds.

Relativity teaches us that the knowledge an observer can have about a system to which he or she belongs is limited. When we are immersed in our own system, we can become blind to events outside of our immediate experience, and we may not be able to easily detect developments in our system (e.g., culture change, unconscious bias) that outsiders might observe much more readily.

Just as we require a frame of reference in order to notice the rotation of the Earth, we can frequently benefit from an external perspective, whether through formal observational methods, independent research, or even through an outside consultant, coach, or therapist. We must be open to other perspectives if we want to truly understand ourselves and our environment.

“Your personal experiences make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world but maybe 80% of how you think the world works.”

Morgan Housel, investor

***

We can also draw inspiration from relativity to practice more empathy; our concepts of “rationality”, “morality”, or “duty” can be highly relative to the contexts we live in. Before we pass judgment or claim to truly understand something, we should pause to consider alternative perspectives. Ask experts from various backgrounds. Seek out the best arguments against your ideas. The perspective that led us to our initial conclusions is rarely the only valid perspective to take!

Notes

- Deutsch, D. (1997). The Fabric of Reality. Penguin Books. 74.

- Feynman, R., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (2010). The Feynman Lectures on Physics (3rd ed., Vol. I). Basic Books. 17-1.

- General relativity: The most beautiful theory. (2015, November 27). The Economist.

- Feynman, R., et al. (2010). 16-3.

- Rovelli, C. (2016). Seven Brief Lessons on Physics (S. Carnell & E. Segre, Trans.). Riverhead Books. 7-11.