Complex systems—such as organizations, governments, ecosystems, planets, or galaxies—tend to exhibit different properties and, consequently, to behave differently depending on their current relative size. Put simply, things that happen at a smaller scale may happen very differently—or not all—at a larger scale.

If scale didn’t matter, then all relationships would be linear. More of one thing would mean more of another—infinitely. For instance, if rain is good, we should want infinity rain. If donuts are good, we should eat infinity donuts. Such reasoning is clearly flawed.

In reality, having more (or less) of something is not always better (or worse); rather, which way you should go depends on where you already are.1 We want more rain during a drought, but not during a flood. The first donut is delicious; the twelfth might cause problems. This is called nonlinear reasoning—a critical tool for any individual hoping to be less wrong.

Understanding the dynamics of nonlinear effects at scale can help us build more successful businesses, programs, and policies—and avoid catastrophe.

The nonlinearities of scale

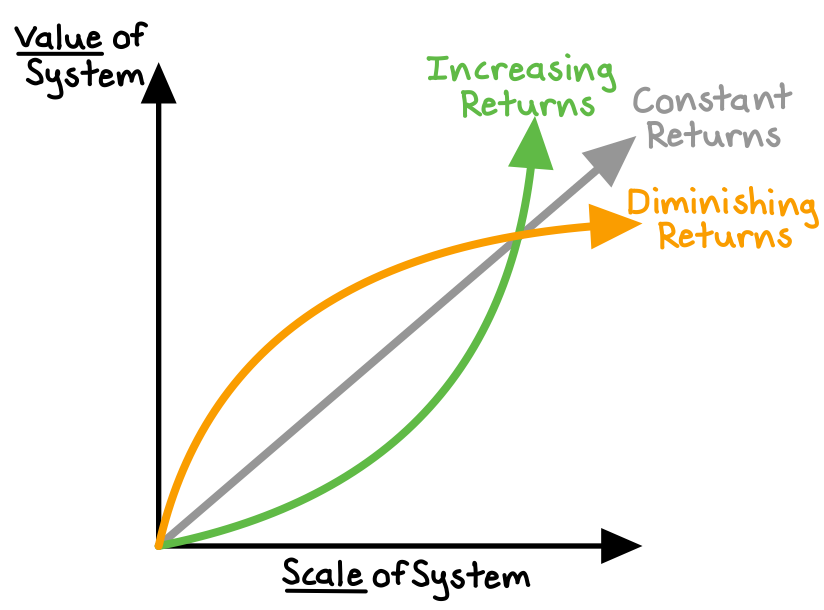

Infinitely linear (“constant”) returns to scale are rare. More often, growth involves increasing returns or diminishing returns—or likely both, given time.

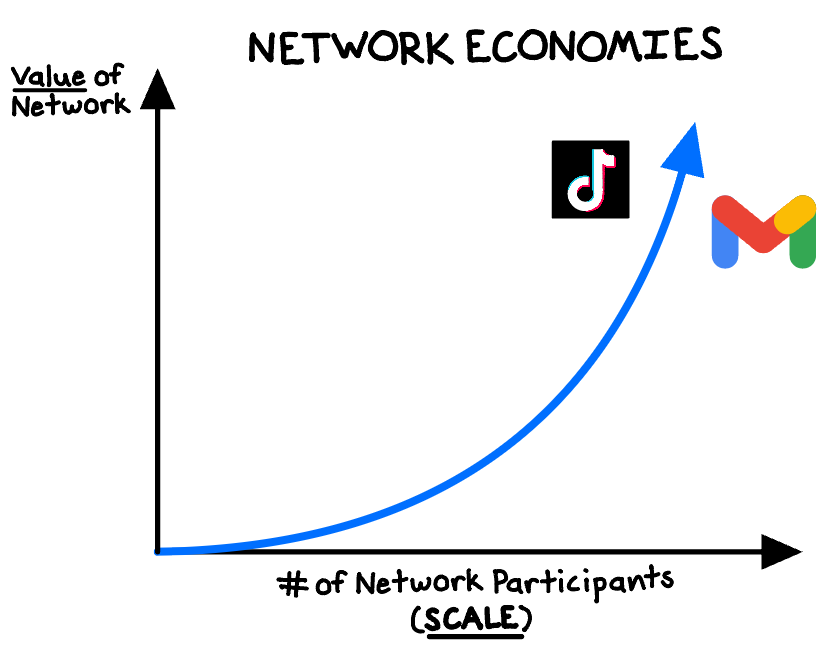

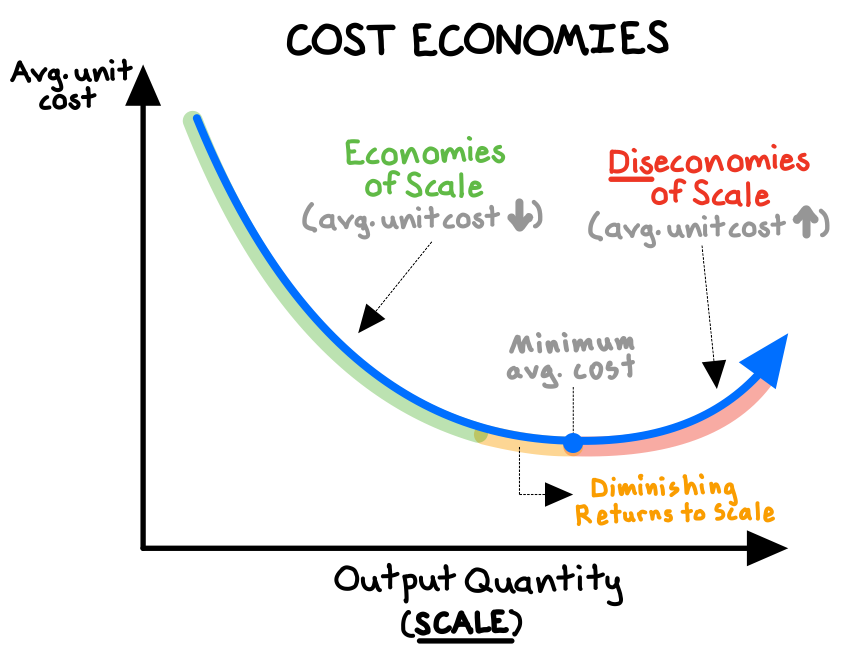

In business, key examples of increasing returns include economies of scale, whereby the average cost of all units declines as production volume increases (e.g., Costco, Tesla), as well as network economies, where each additional user makes the whole network more valuable to all other users (e.g., TikTok, Gmail).

Critically, most real-world results—from donuts, to rainfall, to business—eventually suffer from diminishing returns to scale. With economies of scale, for instance, a growing company cannot decrease its unit costs forever. Beyond a certain size, diminishing returns will tip into “diseconomies of scale,” when a firm’s unit costs increase. Diseconomies might emerge due to managerial limitations, swelling bureaucracy, or increasing scarcity (and thus higher costs) of key inputs, such as raw materials or specialized talent.

So, we’ve established that things change at scale. Let’s explore how to use these principles to build our own ventures.

My idea is scalable… right?

If we care at all about the size of our impact, we need to be able assess the potential scalability of an idea, policy, or program.

“Put simply: you can only change the world at scale.”

John List, The Voltage Effect (2022, pg. 9)

Successfully scaling requires taking an idea from a small group (of customers, units, employees, etc.) to a much larger group, in a healthy and sustainable way.

Fortunately, in his fantastic book on scaling, The Voltage Effect, economist John List proposes five scalability “vital signs” to analyze:

Vital sign #1: False positives

Early evidence may convince us that something is true, when in fact it isn’t—whether due to statistical errors or to human bias.

For example, based on some tentatively encouraging early research, the “D.A.R.E.” program, a zero-tolerance anti-drug campaign championed by the Reagan administration in the 1980s, was scaled to 43 million children over 24 years. Eager politicians jumped aboard to proclaim themselves as pro-kids and pro-cops. The problem: every major study on D.A.R.E. found that the program didn’t actually work, and in some cases actually increased drug use. Unsurprisingly, the program lost federal funding in 1998.2 The false positive signal that convinced leaders to prematurely scale D.A.R.E. nationwide wasted billions of dollars and decades of time and effort by students, administrators, scientists, and legislators.

Because we humans, regardless of intelligence level, often fail to adequately critique our own ideas, we are prone to confirmation bias. This helps explain the occurrence of false positives, as we simply avoid information that challenges our preexisting or preferred beliefs.3 We cannot afford to make this error at scale. We must bring a critical perspective to our own ideas and a healthy skepticism towards whether positive early results are likely to be replicated at scale.

Vital sign #2: Knowing your audience

There is always a risk that the individuals who participate in a pilot study or survey will behave in ways particular to that group. Inevitably, when we scale something to new groups, different people will behave differently.4

If a social media platform such as Twitter, for example, launches an experimental new feature to a small subset (say, 1%) of users to assess the feature’s potential, it needs to be keenly aware of the potential for selection effects—the risk that the sampled users are not representative of the full user population (i.e., that the sample is not truly randomized). For instance, users of the new feature might disproportionately be die-hard Twitter users, or they might be younger and more tech-savvy than the broader user base. Such biases could skew the pilot results to be overly optimistic, giving an illusion of scalability.

We must understand exactly who our idea is for in order to assess its potential for scalability. The characteristics of our early adopters might be very different from our target market at scale.

Vital sign #3: The chef or the ingredients

For an idea to scale successfully, we need to identify our true performance drivers and do everything we can to cultivate and protect them. In particular, is it the “chefs” (indispensable individual humans) or the “ingredients” (the product or idea itself)?

- Chefs — Simply put, humans with unique skills don’t scale. Individual-reliant ideas have a ceiling to their scalability. If key people are overloaded, an organization can atrophy. This is why elite chefs focus more on quality and reputation for one restaurant (or a few), versus on expanding to many locations—where their unique talents would be hard to replicate.

- Ingredients — We must determine what elements we cannot live without—and whether they are scalable. For instance, if quality is a critical ingredient, quality standards cannot decline as we grow. Or if faithfulness to a particular mission is a must-have, we cannot allow drift from the original intent at scale. This “program drift” plagues governmental and philanthropic programs in particular, often due to multiple funding sources each pushing their own agendas.5

Vital sign #4: Externalities (“spillovers”)

The larger the scale, the greater the potential for unintended consequences, or “externalities.” When many individual decisions accumulate and interact, equilibrium may be disrupted and spillovers are inevitable—potentially working for or against our intended outcome.

As a negative example of spillovers, the flagship 1968 federal law requiring seatbelts to be worn in cars actually caused drivers, feeling safer, to take more risks while driving—wiping out the safety gains from wearing seatbelts.

In contrast, a positive example is achieving “herd immunity” from a disease through mass vaccinations. At scale, when a critical portion of the population receives a vaccine, positive spillovers emerge as unvaccinated people still benefit indirectly since a substantial share of the people around them are now immune.6

Positive spillovers scale incredibly well. As with herd immunity, achieving spillovers may even become the objective. Equally powerful, negative side effects can be worse than the original symptoms. As best we can, we should think about what second- and third-order consequences might emerge if we scale our idea, and be prepared to deal with unintended consequences.

Vital sign #5: The cost trap

Regardless of how good an idea is, if the returns on your product don’t exceed the cost, or if the benefits delivered by your program don’t support the expenses, the idea is not scalable. As we learned above with economies and diseconomies of scale, our cost profile can change dramatically at scale—for better or for worse.7

***

The overarching lesson is that when we are dealing with complex systems, we should always establish the scale at which we are analyzing the system—in “orders of magnitude,” at least (hundreds, thousands, millions, etc.). Any insight that applies at one scale may be different or even opposite at another scale. And before we invest substantial time and resources to scaling our ideas, we should critically evaluate whether the idea has the vital signs of success.

Notes

- Ellenberg, J. (2015). How Not to Be Wrong. The Penguin Press. 23-24.

- Ingraham, C. (2017, July 12). A brief history of DARE. The Washington Post.

- List, J. (2022). The Voltage Effect. Currency. 23-33.

- List, J. (2022). 54-64.

- List, J. (2022). 74-84.

- List, J. (2022). 85-91, 101-105.

- List, J. (2022). 109-120.